The Pakistani economy is in shambles. Global creditors like the IMF, the World Bank, and bilateral partners are demanding long-overdue structural reforms, and the country is bracing for a massive financial default if they don’t get them.

These multilateral and bilateral creditors have made it clear that they will only provide financial assistance to Pakistan if the government enacts reforms; they cite the country’s low credit ratings, high debt sustainability risks, and weak macroeconomic situation as reasons for this stance.

Pakistan has massive debt—around US$125 billion outstanding to foreign creditors as of 2023, with about a third of that amount owed to China—which is the main cause of its economic problems.

Accusations that Beijing is pursuing “neo-colonial ambitions” through its alleged “Debt Trap Diplomacy” in Africa and Asia have once again come to the fore as a result of this.

According to experts, Beijing has been lending billions of dollars to economically fragile nations with big populations and a widening infrastructure funding gap. This is a sign of Beijing’s increasing financial influence.

As a result of this policy, many believed that China was actively encouraging the poorer nations to become more dependent on its loans, which were seen as predatory due to the ambiguous terms and circumstances that accompanied them.

In his 2017 article “Debt Trap Diplomacy,” Indian strategist Brahma Chellaney argued that China’s military expanded its influence by coercing debtor nations into giving up important assets and resources through the strategic use of debt. As proof, consider Beijing’s 99-year lease of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port and other infrastructure assets across Africa.

Chinese BRI Supports Nations Most in Need

It has come to light that China has enticed weak nations for its neocolonial ambitions through its much-touted transcontinental Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The utilization of “Chinese companies…Chinese engineers, Chinese workers, and Chinese equipment” is typically an unspoken condition of Chinese loans to borrowing nations.

Several lower and middle-income states have accumulated nearly US$385 billion in ‘hidden debts,’ according to a US-based AidData Lab report reviewing 13,000 projects under the BRI.

These projects were mainly for infrastructure development, including constructing roads, highways, bridges, and hydropower dams. The report’s valuation was US$843 billion, covering 165 countries.

According to Keith Bradsher of the New York Times, “many nations are pushed to the brink” by a sluggish economy and increasing interest rates, causing many nations to struggle to service their debts.

For Pakistan, the picture is similar; after all, the nation owes more than a third of its total foreign debt to Beijing, making it the biggest debtor state to China.

Throughout its seven decades of existence, Pakistan has been governed by the military, which has led to misguided regional policy pursuits and a dismal socioeconomic infrastructure.

It served as an almost ideal model for Chinese enticement, which, under the BRI, pledged to improve and raise basic infrastructure.

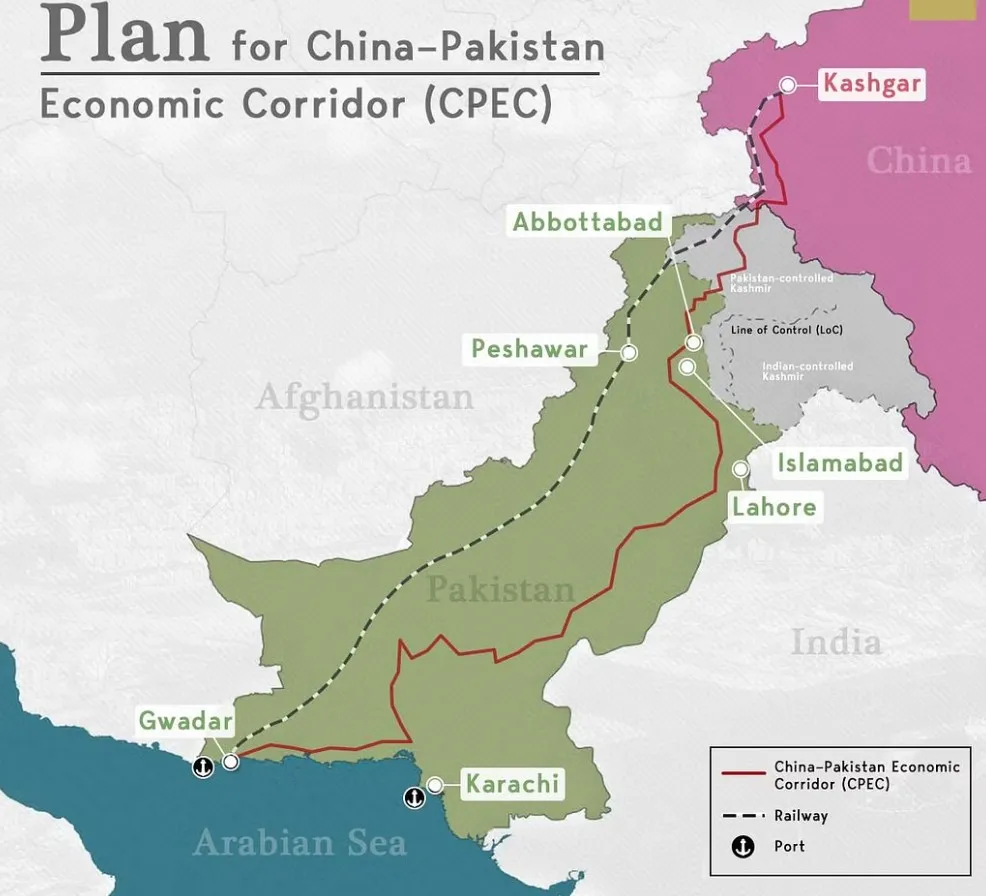

With Pakistan’s 2013 accession to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s predatory lending reached exponential heights; the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the project’s most vital component, began with an initial budget of $45 billion but has now ballooned to more than $62 billion.

The Almost Perfect Debt Trap in Pakistan

With an estimated project cost of over US$25 billion, the Pakistani portion of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is the largest contributor to Pakistan’s mounting foreign debt. This means that Islamabad owed Chinese creditors this amount of money upfront.

Most of China’s aid to Pakistan has gone toward “infrastructure and energy investments,” but the character of this aid has been particularly noteworthy.

Despite what successive Pakistani governments supported by the military establishment would have you believe, Beijing’s investments in Pakistan were loans and not handouts, contrary to widely held beliefs and skillfully crafted public views.

Much more worrisome is that Pakistan obtained these loans at flat commercial rates above 5% and, in many instances, over 7%—much more than other international financial lenders like the IMF, which lends at 2%.

Islamabad is having trouble keeping up with its debt service because of the debt spiral that Pakistan has fallen into due to these much higher interest rates. Debt servicing in Pakistan has not been able to repay the same interest rates as original borrowings, a sign of how viciously the country’s debt has accumulated.

Pakistan owes China $40 billion; even using a modest 5% interest rate, the interest component of this debt would still leave the country with $2 billion.

As an example, according to the State Bank of Pakistan, Pakistan will have to pay back $20.81 billion (PKR 792 lakh crore) in foreign debt in Fiscal Year 2023. This figure includes a massive interest payment of $4.42 billion (PKR12.46 lakh crore).

Because of its low credit score and its inability to meet the demands of foreign lenders—including micro-cum-macro economic reforms and an improvement in its tax collection regime—the country is dependent on China for financial support and must keep vital sovereign wealth reserves on hand to guarantee its short-term viability.

Repaying the previous loans at the interest rates set by Beijing—mainly commercial lending rates—will require Pakistan to take out new loans from China. An example is the US$600 million loan that Pakistan reportedly discussed with the Bank of China and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) on November 8.

This pattern persists from 2017, when Pakistan began to borrow money from Beijing to repay the debts it had received as “grants” under the CPEC for development.

Pakistan’s dire economic predicament, which could lead to a financial default, is a result of its massive debt, most of which is owed to Chinese lenders.

China appears pleased to keep Islamabad afloat like a sick patient on essential ventilator support, effectively encircling Pakistan in a vicious debt trap loop.

Despite appearances, thanks to this generous support, China is strategically positioned to dictate terms and acquire key strategic assets. This suggests a dismal future for the nation, which can affect both the country and the surrounding area.