NEW YORK – A Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Central Harlem, New York City, has caused growing concern among health officials. As of August 4, 2025, there have been over 50 confirmed cases and two deaths linked to this event.

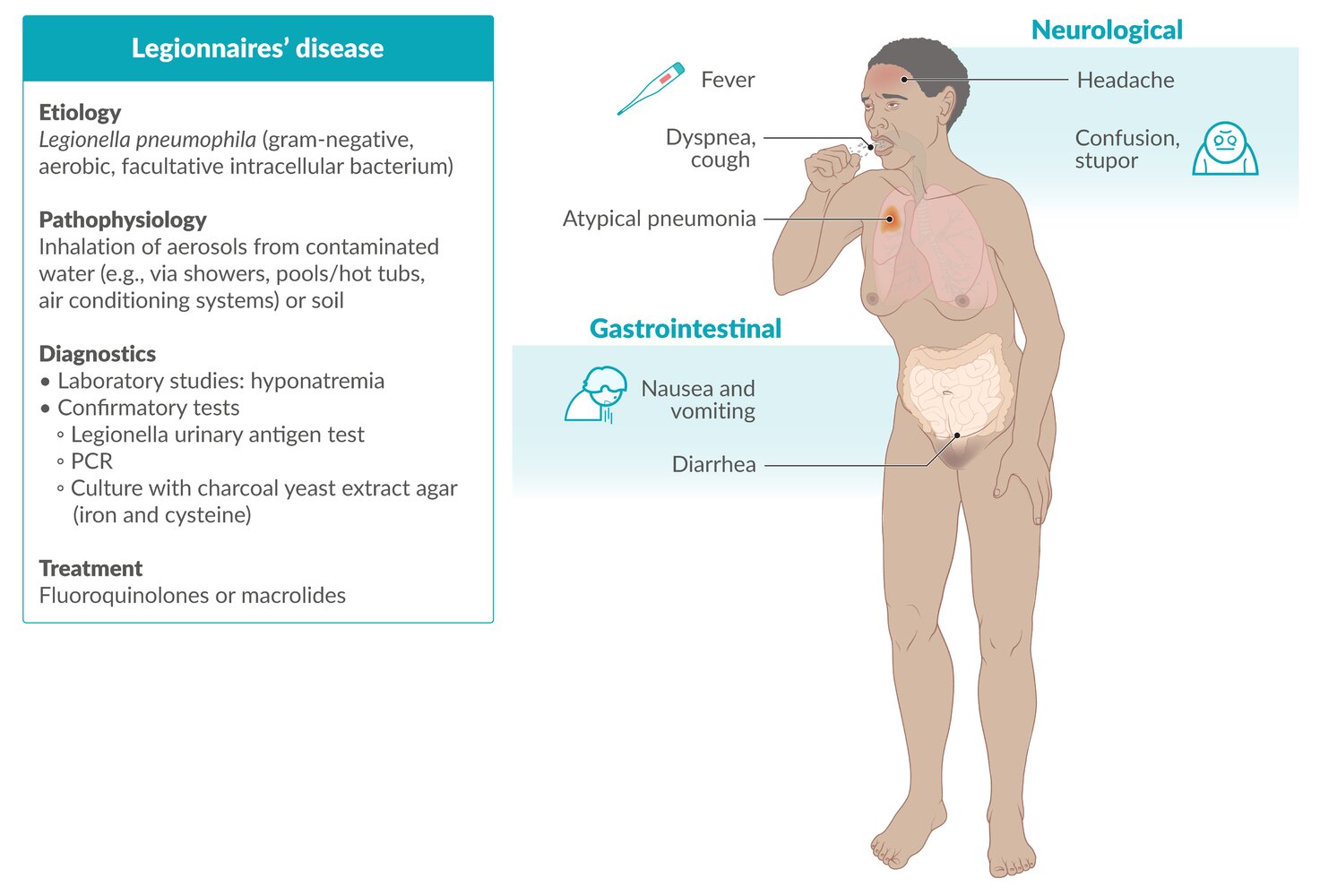

Legionnaires’ disease is a severe type of pneumonia caused by Legionella bacteria found in water. This incident highlights the challenge cities face with controlling waterborne bacteria.

Local authorities are working to stop the spread, but residents and building owners need to stay aware of how this illness spreads, what symptoms to look for, and ways to protect themselves.

Details of the Outbreak

The outbreak first came to light on July 25, 2025, with cases spread across five Central Harlem postcodes: 10027, 10030, 10035, 10037, and 10039. Health officials believe cooling towers in the area are the most likely source.

Routine checks showed that 11 cooling towers contained Legionella pneumophila, the main type of bacteria causing the disease. These towers help cool buildings by releasing water vapour, but if not kept clean, they can become a home for bacteria. Tiny droplets carrying the germs can linger in the mist, which people may breathe in.

Across the United States, Legionnaires disease affects between 8,000 and 18,000 people each year. The last two decades have seen more cases, possibly due to ageing water systems, warmer temperatures, and better testing. For example, Minnesota saw 134 cases with six deaths in 2023. The Harlem outbreak fits into this wider trend of increasing cases.

How Legionnaires Disease Spreads

People catch Legionnaires disease by breathing in mist or vapour containing the bacteria. Legionella thrives in warm, still, water found in cooling towers, hot tubs, showers, and decorative fountains. The illness does not usually spread from person to person, but it can be caused if water accidentally goes into the lungs, especially in people who have trouble swallowing. Drinking contaminated water does not usually cause infection.

Most outbreaks are connected to large water systems in places such as hospitals, hotels, or apartment blocks. For instance, in 2015, the Bronx saw 138 people fall ill, and in 2019, a fair in North Carolina reported 141 cases, some linked to a hot tub display. The situation in Harlem is similar. While the general risk is low, authorities advise people in the affected areas to be cautious.

Legionnaires Disease Symptoms

Those infected can start to feel ill between two and ten days after exposure, but rare cases may take up to 20 days. The first signs of Legionnaires disease are much like the flu, such as:

- High fever, often 104°F (40°C) or more

- Chills

- Muscle pain

- Headaches

- Feeling very tired

- Dry cough

If it becomes worse, the illness can turn into a serious lung infection. This can cause trouble breathing, chest pain, and, less often, coughing up blood-stained phlegm. Some people might also have stomach problems like feeling sick or diarrhea, or confusion.

Left untreated, Legionnaires disease can get serious quickly and may lead to breathing failure, very low blood pressure, or kidney failure. Treated cases have a death rate of 5-10 percent, but this is much higher for people with weak immune systems.

A milder illness called Pontiac fever can also be caused by Legionella. This version has flu-like symptoms but does not cause pneumonia and usually clears up in less than a week without needing treatment.

People Most at Risk

Most healthy people do not get sick if exposed, but some are more likely to develop Legionnaires disease. These include:

- Adults over 50

- People who smoke or who have smoked in the past

- Anyone with long-term lung disease, such as COPD or emphysema

- Those with weakened immune systems from illnesses like cancer, diabetes, HIV, or kidney disease

- People taking medicines that suppress the immune system, such as after an organ transplant

Residents of care homes or those who have just come out of the hospital are also more at risk. In the Harlem outbreak, all reported cases were adults, and 11 needed hospital treatment.

How to Protect Yourself

There is no vaccine for Legionnaires disease, and antibiotics do not stop people from getting it if they have not been exposed. Still, individuals and building owners can help prevent infection.

For individuals: Clean and disinfect showerheads, taps and hot tubs regularly. Do not use plain water in the car windscreen wiper fluid, as bacteria can grow there. If an outbreak is happening nearby, get medical help straight away if you have symptoms, especially if you are in a higher-risk group. Let your doctor know if you have travelled or used hot tubs or cooling towers recently.

For building owners: Keep water systems managed and checked. Water heaters should be set at least 120°F (ideally closer to 130-140°F with care taken to prevent burns). Cooling towers and plumbing should be tested and disinfected on a regular schedule. In New York City, cooling towers need to be registered and checked for Legionella according to local rules.

Public health advice: Health departments recommend following CDC guidelines for keeping water systems safe. During outbreaks, environmental testing and matching bacteria from patients with samples from the environment can help find the source.

Treatment and Recovery

Legionnaires disease can be treated with antibiotics like levofloxacin or azithromycin, usually for 5 to 10 days. People with weak immune systems might need treatment for longer. Early diagnosis, using chest X-rays, urine tests, or lab cultures, can improve the chance of a full recovery.

Most patients get better with prompt treatment, but severe cases might need intensive care. Some may face ongoing lung or brain problems after recovery.

The Harlem cluster shows how important it is to look after water systems to stop Legionella bacteria growing. As Dr Celia Quinn from the NYC Health Department said, most people are not at high risk, but anyone with symptoms should get checked right away.

With cases rising in the US, stronger rules, better awareness and faster diagnosis will help reduce illnesses and deaths from this preventable disease.