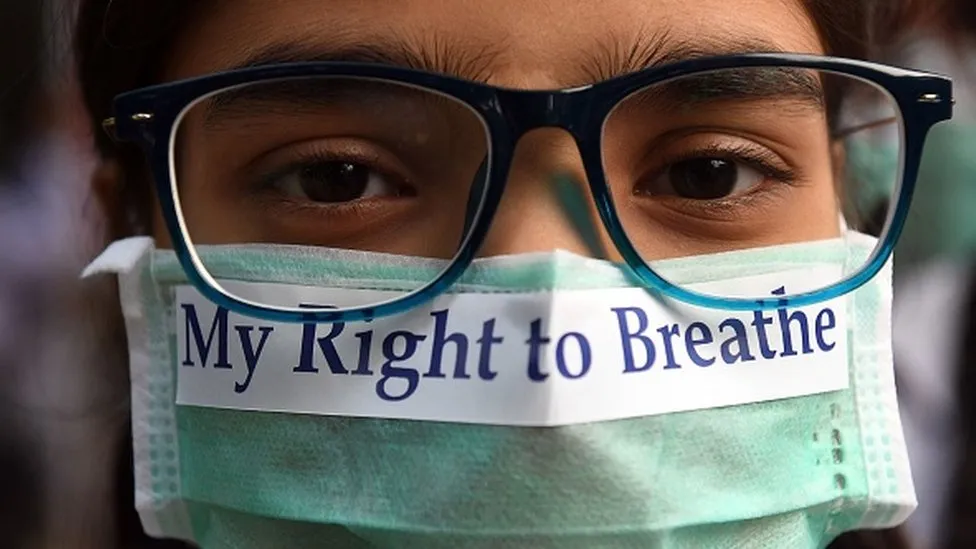

(CTN News) – While the pollution issue in Delhi, India’s capital, has recently garnered international attention, it is far from new. The highest court in the land has deliberated the matter at length for nearly forty years, sometimes issuing rulings that have drastically altered daily life in Delhi.

In early November, the Supreme Court demanded “immediate action” in response to the dangerously low air quality in the nation’s capital, marking its most recent intervention.

The Delhi government’s efforts to address the situation were discussed in court. These included a plan to limit the use of motor vehicles on certain days based on the last digit of license plates, as well as a reduction in stubble burning in neighboring states of Punjab and Haryana.

Last Monday, the court reprimanded authorities for what it deemed a “gross breach of assurances” in failing to implement its directions to distribute funding for a rapid rail system, even though it left the discretion of developing these policies to the government.

The project’s goal is to reduce traffic congestion by linking Delhi to nearby cities via high-speed rail tracks.

The top court criticized the state government of Punjab for its inaction in preventing stubble burning and for the negative portrayal of farmers in the state as a result.

The Supreme Court has been a pioneer in air pollution measures in Delhi, issuing directives such as limiting the types of cars allowed on city streets, forcing the transfer of thousands of polluting companies, and closing off polluting businesses.

Despite its reluctance, it has also received praise for compelling the administration to take action.

The effectiveness of the court’s rulings has been questioned by detractors, who also accuse it of frequently interfering with presidential actions. Some have noted that the capital’s pollution levels have increased over the last four decades despite efforts to address the issue.

A renowned lawyer named Shyam Divan recently wrote that the highest court in India fulfills the several roles of “policymaker, lawmaker, public educator and super administrator” simultaneously.

Americans have the US Congress, the EPA, and a plethora of funds to safeguard the environment. “This is where our Supreme Court is located,” he declared.

But many who support the court see it as a watchdog and a place where people can work out their differences.

In 1984, environmentalist MC Mehta brought several complaints to the attention of the highest court over pollution in Delhi, specifically regarding the increasing pollution caused by vehicles in the city, the effects of this pollution on the world-famous Taj Mahal, and the contamination of the rivers Ganga and Yamuna.

The court has been adding additional issues to these pending petitions; for example, in 2017, it combined a request regarding the smog problem in Delhi with an ongoing case over vehicle pollution.

The court has also occasionally taken very extreme action.

The government mandated 1998 that all diesel-powered public vehicles, numbering an estimated 100,000, convert to compressed natural gas (CNG) by 2001.

Court fines and the threat of contempt kept everyone in compliance, even if the government was against the change.

For example, the court froze the licenses of tuk-tuk drivers for over a decade, and it has also gotten into smaller details like what types of vehicles should operate in Delhi.

The actions yielded results, but only temporarily. Research confirms that switching to CNG helped improve air quality in Delhi.

Nevertheless, according to experts, these benefits have been overwhelmed by the surge in private vehicles in the city.

Millions of people, including tuk-tuk drivers and others in the public transportation industry, were negatively impacted by the ruling, according to lawyer Anuj Bhuwania’s book Courting The People. These people were never allowed to state their case in court.

Once hailed as one of the “most powerful weapons” to effect social change, he claims that a small group of attorneys and plaintiffs in India’s public interest litigation system have taken control and are pushing for reforms at the expense of low-income people.

“At this point, if they [the court] washed their hands off it, we may not be worse off because they’ve done so much damage,” said Mr. Bhuwania.

However, some judges think the court should step in, and they have a track record of success.

A former chief justice, PN Bhagwati, who presided over environmental cases and helped bring the court into policymaking, predicted that “judicial activism” would be unavoidable.

Although the court’s rulings have inconvenienced many, another former chief justice, KG Balakrishnan, stated that the judges’ willingness to take “unpopular decisions” to clean up the environment was demonstrated by the initial success of the CNG order.

While the court’s goal of improving the city’s air quality has been admirable, some legal experts have raised concerns about the soundness of some of its rulings.

A federal court ordered the installation of smog towers—large-scale air purifiers—in the nation’s capital in November 2019.

According to multiple experts who spoke with the BBC, there wasn’t enough proof at the time that these towers would reduce air pollution. Even the capital’s pollution control board reviewed the towers four years later and said they were useless.

But not everyone thinks things have become worse because of the Supreme Court.

According to environmental lawyer Shibani Ghosh, there have been some tangible benefits from the court’s involvement.

It “has to allow the government to take the lead,” she continued when it comes to implementing policies and new legislation.

According to environmental law expert Ritwick Dutta, specialty tribunals or lower courts could be crucial in upholding current environmental legislation.

India has enacted many additional regulations during the past forty years to curb deforestation, wildlife poaching, water contamination, and noise pollution.

“Even the Supreme Court, which has taken the lead in Delhi, listens to the case only when pollution is at its peak in the city” , said Mr. Dutta.

“But the moment the air quality improves, the cases are once again put on the backburner.”