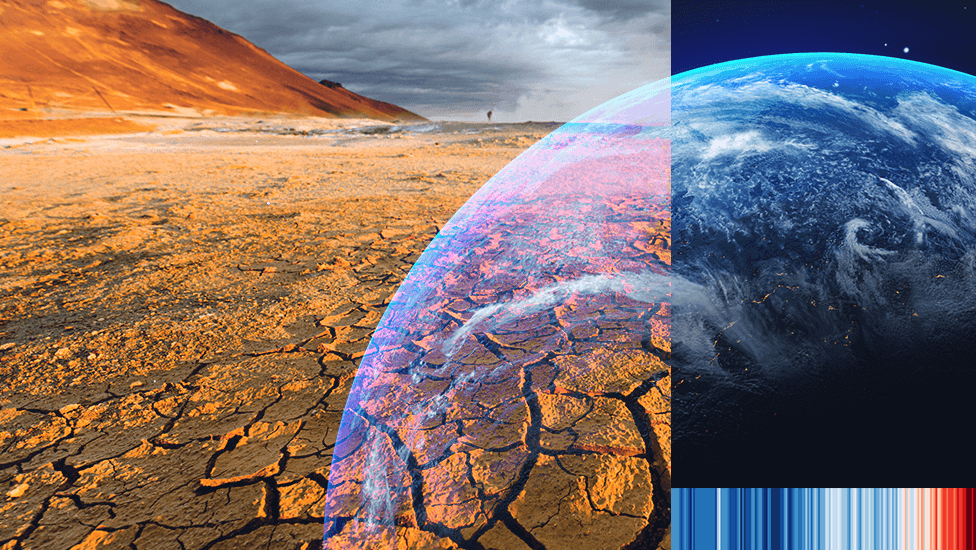

(CTN News) – In Australia, most discussions on climate action revolve around emissions reduction. However, cutting emissions is only one aspect of the climate story; Australia must also plan how to adapt to the effects of climate change. Nations’ resilience to climate change is determined by adapting to increasing sea levels, preparing for heatwaves, and managing shifting rainfall patterns.

The floods that devastated north Queensland in December 2023 and northern New South Wales (NSW) in 2022, as well as 2020’s Black Summer bushfires, demonstrate that Australia must step up its conversation about how it intends to adapt to the effects of climate change.

However, in Australia, where climate change has been a long-standing political issue, legislative progress on climate adaptation has been gradual.

As the Australian government prepares to release its Issues Paper for its first National Adaptation Plan in the coming months, it’s a good moment to consider why the country has lagged on climate adaptation legislation — and what’s required to make its plan successful.

National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) are a valuable tool for determining climate adaptation priorities at the country level. They were created to speed up adaptation planning at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) COP16 in 2010. Since then, around 70 countries have developed one.

While the most developed countries (including Finland, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand) and approximately 40 developing countries (including Chad, Fiji, and Sudan) have produced plans, Australia has made slow progress on climate adaptation.

Under the Morrison Coalition government in 2021, Australia submitted a National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy to the UNFCCC. However, it was never legislated and consisted primarily of existing projects.

The Albanese Labour government pledged a large commitment to climate change adaptation in its 2023-2024 budget, particularly emphasising completing a National Climate Risk Assessment and National Adaptation Plan.

That strategy is already in the works: the government plans to present an Issues Paper in early 2024, following consultations in 2023. This will support broad public consultation throughout 2024, with the NAP expected to be completed in time for the COP29 summit in Baku in November 2024.

Australia has lagged in climate adaptation because climate change and research have long been political footballs.

The country got off to a promising start with the 2007 National Climate Change Adaptation Framework approved by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), followed by large investments in the National Climate Change Research Facility. However, with a change of government, climate change became a marginalised subject for many years.

When then-Prime Minister Scott Morrison unveiled his 2021 climate adaptation strategy, he was chastised for hiring multinational consulting firm McKinsey, which has advised 43 of the top 100 corporate polluters, to do the modelling rather than Australia’s national science agency, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

Climate adaptation has not been prioritised due to other policy concerns. However, Australia’s poor progress towards building a NAP is partly based on the misconceptions that focusing on adaptation diminishes ambition to cut emissions and that adaptation is primarily a local issue that should be addressed at the local government level.

These are both incorrect. Adaptation and mitigation are both critical climate measures, and all levels of government have a role in adaptation.

These assumptions are currently changing. There are numerous chances for diverse stakeholders to take the lead in climate adaptation. Many state and municipal governments have already produced climate adaptation plans and strategies, indicating a growing awareness that urgent climate adaptation is required.

Critics of the NAP dispute if the Albanese government’s multimillion-dollar expenditure is worthwhile. However, there are various ways in which a true national strategy, rather than just local and state policies, may help Australia.

Without an adaptation strategy, a country would struggle to grasp its risks, priorities, and progress.

Making judgements and national policy without a complete NAP is likely to ignore the effects of climate change, skewing planning budgets by failing to include expenditures for damages.

For example, Australia can commit to long-term infrastructure improvements that appear economically reasonable, but if the effects of climate change on that infrastructure are ignored, the plan will result in increased vulnerability.

Building new roads in a changing environment, for example, means that building materials may need to endure increasing heat in the future, necessitating a different assessment of current and future costs.

Australia’s adaptation strategy has the potential to shed insight into how climate impacts might exacerbate inequality and unfairness across the country due to the uneven distribution of susceptibility.

Without a NAP, policies may present a misleading picture of the causes of inequality and the potential for current policies to address it.

Any growth in inequality can have serious ramifications for people’s security and, possibly, political stability. NAPs are crucial for measuring climate change adaptation progress, especially tracking how climate adaptation impacts the most vulnerable and marginalised communities.

NAPs frequently highlight critical challenges for researchers and industry, indicating where additional study is required to enable evidence-based decisions and the spectrum of the most promising and scalable adaptation solutions and projects that could accelerate adaptation progress and implementation.

Having an NAP does not guarantee progress in climate adaptation. Key questions for Australia include how the plan will be executed and funded and how priorities will be established and scaled to achieve the greatest reductions in vulnerability.

To properly answer these concerns, there must be a strong emphasis on creativity and a varied range of expertise and experience.

Many countries have made climate adaptation a legal requirement to ensure efforts do not stall due to political changes.

The United Kingdom, for example, has a Climate Change Act (2008), which established the Climate Change Committee and the National Adaptation Programme, as well as regulatory reporting methods and timelines.

This strategy recognises that climate adaptation is more than a “nice to have” when a government feels like it; it is a need with long-term policy support. Australia may surely consider this technique.

Moving forward, adaptation to the effects of climate change must be considered in all areas.

Australia’s agriculture sector may need to plan for food insecurity, which could entail modifying or diversifying crops to promote more water-efficient farming.

The energy sector has a long way to go towards climate adaptation. While there are benefits and chances to capitalise on, for example, Australia is the world’s largest supplier of lithium, which is used in batteries; nevertheless, the country is also a major emitter and provider of fossil fuel resources.

It is not just the world’s greatest net exporter of coal but also the largest exporter of liquefied natural gas, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. Direct mapping of Australia’s emissions and their impact on vulnerability reinforces the need for energy sector change.

There are fears concerning Australia’s distinctive biodiversity. The Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral reef, is threatened, and Australia is the only developed country designated as a deforestation hotspot.

Urban planning and emergency management must both adapt. Change is required, from early warning systems to refraining from building in places prone to bushfires or flooding.

Australia must also consider how the changing nature of disasters and long-term trends, such as droughts, put its population in greater danger. These conversations are crucial for towns with firsthand experience with extreme weather occurrences, such as Lismore. Climate resilience consequently entails planning for the future in a way that enables communities in at-risk areas to be safe and healthy.