BEIJING – A personal dispute at the respected China-Japan Friendship Hospital has exploded into a national scandal, shining a light on issues of privilege, academic dishonesty, and unfairness in China’s top medical circles.

The main figure in the controversy is Dr. Xiao Fei, a former associate chief thoracic surgeon. His affairs and professional misconduct have fuelled public anger and sparked wider debate about inequality in Chinese society.

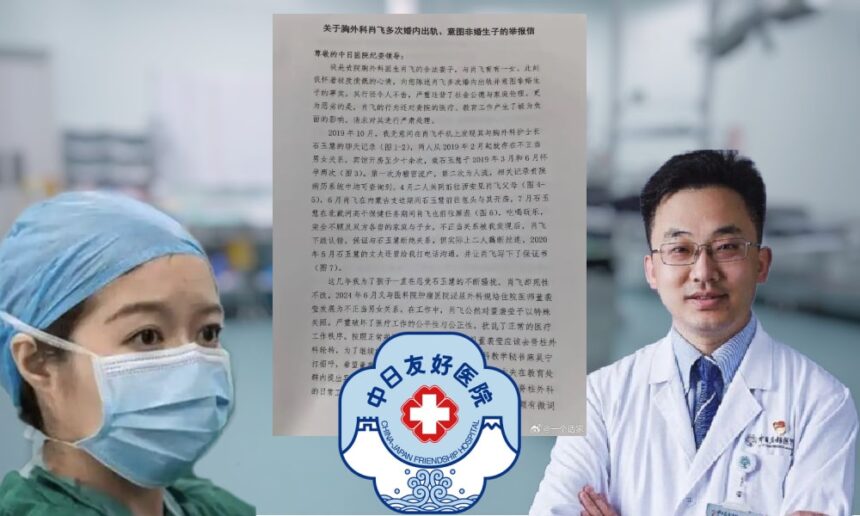

The story broke in mid-April when a detailed letter written by Xiao’s wife, Gu Xiaoya, appeared online. Gu, an associate chief ophthalmologist at Beijing Hospital, wrote to the hospital’s Discipline Inspection Commission accusing Xiao, 38, of having multiple affairs with colleagues, including head nurse Shi Yuhui and resident doctor Dong Xiying.

Supporting evidence revealed Xiao’s actions had crossed ethical lines and damaged public trust. The letter quickly went viral, dominating sites like Weibo and sparking fierce debate, making it the biggest scandal in China this year.

The most disturbing claim was Xiao’s decision to leave a sedated patient alone during surgery in July 2024. Reports say Xiao and Dong walked out of the operating theatre for 40 minutes after arguing with another nurse about a mistake Dong made during the procedure. Leaving the patient unattended breached basic medical ethics. Xiao said he left because he felt dizzy and his hands were shaking, but this excuse did little to calm public anger.

On April 27, the hospital confirmed Xiao’s dismissal, stating that the accusations of “personal and professional misconduct” were “largely true.” Xiao lost his Communist Party membership, and the National Health Commission revoked his medical license on May 15.

Dong Xiying also lost her license, and her academic qualifications were withdrawn due to claims of cheating and plagiarism.

Spotlight on Privilege in China

While much attention has focused on Xiao’s actions, the scandal soon turned to Dong Xiying’s rapid rise in medicine. Dong, who studied economics at Barnard College in the US, entered the hospital’s top medical training scheme without an undergraduate medical degree. Online investigators found that her mother, Mi Zhenli, is a vice president at the University of Science and Technology Beijing.

Her father, Dong Xiaohui, is a senior executive at a state-owned company. Many people believe Dong used the “4+4” pathway, a fast-track route that lets privileged students skip traditional medical training.

This has fuelled a broader debate about fairness and who gets ahead. Social media users have compared Dong’s path to Chen Ruyue, a finance graduate from Peking University who was turned down by the same programme after years of effort. “How can someone with an economics background be called a ‘medical talent’ after just a few years?” asked one Weibo user. “Where’s the fairness in our medical education?”

The “4+4” scheme was meant to attract students who studied abroad, but critics say it lets well-connected families give their children an unfair head start, making it harder for ordinary students to compete. “This isn’t just about one doctor’s affair,” said a senior doctor privately. “It’s about a system that rewards family ties instead of skill.”

This scandal has grown from personal failings to a national debate about privilege, ethics, and deep problems in China’s medical and education systems. Hashtags about the case have pulled in millions of views on Weibo, as people express frustration about how Xiao and Dong’s family links protected them for years. Posts on X have accused officials of ignoring the bigger problems of corruption and favouritism.

The case has highlighted how hard it is for regular medical students. “We study for years, sit endless exams, and still can’t get into top hospitals,” one aspiring doctor wrote online. “Meanwhile, those with wealthy parents walk straight in.” Public trust in healthcare, already shaken by overcrowding and lack of resources, has taken another hit.

Demands for Change

Experts and everyday people are calling for serious reform. Suggestions include a clear national test for doctors, public access to surgical records, and scrapping admission routes that give special treatment to privileged applicants. “This is about rebuilding trust,” said a medical ethics professor in Beijing. “Patients must believe their doctors are skilled, not just well-connected.”

The China-Japan Friendship Hospital now faces a damaged reputation. The scandal has also pulled Peking University’s medical school into the spotlight. Both Xiao and Dong had ties there, raising questions about oversight. The hospital’s “Elite Programme,” which gave Xiao a fast track, is under review for valuing reputation over responsibility.

Amid the outrage, Dr. Ma Haoning has won praise for his honesty. Ma, who works as a teaching secretary in orthopedics and plays keyboard for the band Panini Lin, refused Xiao’s request to block Dong’s transfer to another department. This stand made Ma a popular figure online. “Ma Haoning stuck to his principles,” wrote one Weibo user. “He’s the kind of doctor people want to see.”

As the scandal settles, it highlights how fragile trust is in China’s institutions. Xiao and Dong are facing the fallout from their actions, but the bigger issues of privilege and fairness remain unresolved. Public anger, fuelled by social media, shows people want real accountability and equal treatment in a system seen as unfair.

“This isn’t just about Xiao or Dong anymore,” Gu Xiaoya wrote in her letter, which still circulates widely. “It’s about a society where the privileged bend the rules, while others are left behind.” As China faces tough questions about its future, the hospital scandal could mark a turning point—or stand as a warning of a system slow to change.