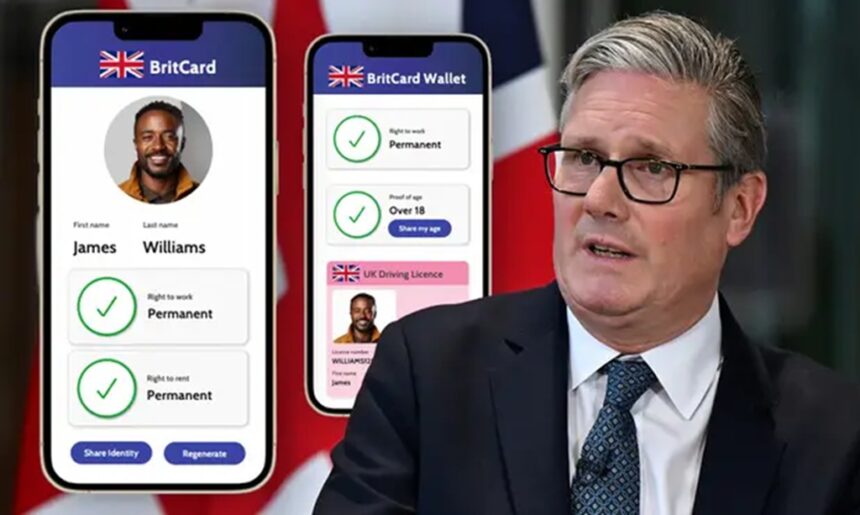

LONDON– Keir Starmer has set out plans for a mandatory digital ID, branded the BritCard, in a pitch to tighten border controls and crack down on illegal work. The New Digital ID scheme would sit on smartphones, similar to contactless bank cards or the NHS app.

Ministers want all working adults to use it to prove their right to work before the end of this Parliament. Starmer called it an enormous opportunity to modernize the state, curb exploitation, and restore confidence in immigration checks. The plan has triggered a fierce backlash that threatens Labour’s standing just 15 months into office.

The BritCard flows from Labour’s drive to get a grip on migration, a running fault line in politics for years. Since Labour took power in July 2024, more than 50,000 small boat crossings have been recorded, up 27 percent on the previous year. Voters put immigration just behind the cost of living as a top concern. The scheme, drawn from a Labour Together report, would verify identities against a central Home Office system.

Supporters say it would make illegal working harder and reduce the pull of the underground economy for smuggling gangs. The Tony Blair Institute backs the plan, arguing it could reduce Windrush-style failures by standardizing right-to-work checks. It could also make daily admin easier, with faster access to services and fewer paper documents.

Digital ID Card Fears

Ministers frame the policy as a practical fix for a system that does not work. Employers face fines of up to £45,000 for hiring people without status, yet many rejected asylum applicants, about 100,000 over 14 years, are thought to remain. Starmer told the Global Progress Action Summit that past squeamishness on migration helped fuel populism, and promised to tackle every part of the issue.

The BritCard would use the One Login platform already rolled out across 50 government services. Officials say it keeps data on personal devices with best-in-class security, not a giant national database. Paper or physical options are being explored for offline people, such as the 1.7 million over-74s. Costs are unclear, with estimates ranging from £140 million for setup to £2 billion for full-scale delivery. Ministers argue it is money spent on a modern, efficient state.

The proposal revives memories of Tony Blair’s ID card plan in the 2000s, dropped in 2010 after public anger and rising costs. The reaction this time has been instant and heated. A parliamentary petition titled “Do not introduce Digital ID cards” passed 1 million signatures within hours.

Campaigners call it a step toward mass surveillance and digital control. On X, critics warn of a slippery slope to social credit. Actor Laurence Fox urged mass civil disobedience. Others fear a return to a papers, please culture.

Polling shows mixed views. Ipsos reported in July 2025 that 57 percent support national ID cards in principle, rising to 66 percent among older voters and Conservatives. More in Common put support at 53 percent across most parties, including Reform UK. Once digital is mentioned, support drops. Ipsos found only 38 percent in favour and 32 percent opposed.

People cite privacy and cyber risks most often. Street interviews reveal deeper worries. Some see tracking and intrusion, while others fear exclusion for the elderly and low-income groups. Big Brother Watch warns about digital discrimination, pointing to COVID-era tech failures that locked out many. High-profile breaches, such as the British Library attack in 2024, add to fears that a central credential could be a rich target for hackers.

BritCard is a High-Risk Move

Opposition parties have lined up to attack the idea. Reform UK’s Nigel Farage called it a cynical ploy that would not stop illegal migration and would hand more control to the state. Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch branded it a gimmick and promised to fight any attempt to force Digital ID on law-abiding citizens.

The Liberal Democrats, who helped scrap Blair’s scheme in 2010, said they cannot back a mandatory rollout. Sir Ed Davey signalled he might soften if strong safeguards are in place, but his party remains wary. In Scotland, First Minister John Swinney condemned a BritCard that he says undermines devolution.

In Northern Ireland, Michelle O’Neill called it ludicrous and an attack on the Good Friday Agreement. On Labour’s left, MP Ian Byrne said the plan is tone deaf and unpopular. Former Home Secretary David Blunkett urged Labour to go further but admitted the rollout has been muted.

Liberty warned it would exclude vulnerable people and centralize highly sensitive data.

Electorally, the BritCard is a high-risk move before 2029. Starmer presents it as a shield against Reform UK, with Farage leading in polls and peeling away working-class voters over migration fears. If the system cuts illegal working and speeds up services, it could blunt Reform’s grievance politics, as Starmer puts it, and firm up Labour’s vote around 34 percent.

Polly Toynbee argued in The Guardian that it could be Labour’s secret weapon, signalling pride in British identity and challenging Farage on border control. The downsides are obvious. The plan was not in Labour’s manifesto, which angers privacy campaigners and parts of the left. It could drive away urban progressives and feed claims of a snooper state.

The Last Thing People Need

Social media outrage is already intense, boosted by libertarian voices abroad. Florida’s Ron DeSantis promised to block similar moves in the US, calling for a brick wall against digital ID. Any early glitches could echo Blair’s billion-pound fiasco and sap trust in a government under pressure on public finances. Polls show support fades under scrutiny.

If costs rise or data leaks occur, Labour’s thin majority could splinter, opening the door for Reform in Red Wall seats.

For Starmer, the row is a test of authority. The former prosecutor, praised for competence, now faces a party split over winter fuel cuts and the two-child cap. Support from the Blair Institute signals a centrist tilt, but alienating MPs like Byrne risks unrest on the left.

In his summit speech, he linked the policy to progressive patriotism and attacked what he called industrialized grievance from Trump and Farage. Critics such as Jim Killock of the Open Rights Group say a digital ID is the last thing people need during a cost-of-living crisis. Success would badge Starmer as tough on borders and competent on delivery.

Failure would invite Blair 2.0 headlines, accusations of a database state, and comparisons with China’s surveillance systems. One user on X claimed Britain is slipping under digital chains. With consultation rounds due, the government must prove it can improve security without eroding basic freedoms.

The fate of the BritCard depends on that balance. For now, it crystallizes Labour’s reckoning on immigration. It could be a practical fix for long-running problems, or the start of a surveillance regime most voters do not want. The debate is not going away.