BANGKOK – Thailand’s Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra has given officials three months to show real results against combating cybercrime and scam gang networks operating from Cambodia.

She led a meeting on Monday with police and security teams to review ongoing scams, including call centres based in Cambodia. Cambodia has become a hotspot for cybercrime groups targeting people across the world.

After the meeting, Ms Paetongtarn said the government will step up its response to organised cybercrime, which threatens both security and the economy. She said some steps are already in place, and Thailand has tightened border rules to stop gamblers from travelling to Cambodian casinos and has cut off some internet links tied to scams.

The prime minister also mentioned the option of stopping fuel and energy sales to Cambodia. However, Cambodian leader Hun Manet has already moved to stop these imports from Thailand as of last weekend. Paetongtarn said Thailand’s actions have cost the scam rings in Cambodia about 30 million baht.

On a related note, Police Inspector-General Tatchai Pitaneelaboot announced that Thailand will host a meeting of police chiefs from all 10 ASEAN countries at the end of July to tackle cross-border scams. He shared that criminals have tricked or recruited people from 36 countries to work in call centres in Myanmar and Cambodia.

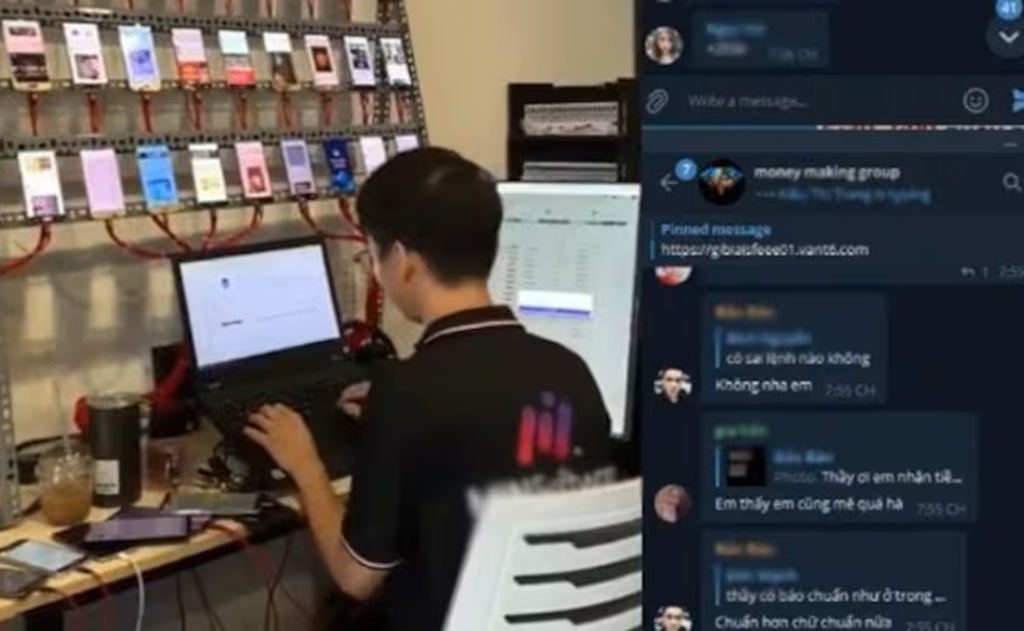

Scam Gangs in Cambodia

Victims are often young, skilled with technology, and come from countries like Vietnam, Thailand, India and China. They are drawn in with fake job adverts that promise high wages.

Once they arrive, they are trafficked into locked compounds, stripped of their documents and forced to run scams under threats and violence. Many suffer beatings, electric shocks or starvation if they miss targets, while some are sold to other groups or held for ransom.

The United Nations estimates that over 100,000 people are trapped in these operations in Cambodia, facing abuse and, in some cases, death.

These scam groups continue to grow due to weak laws, bribes and links to influential figures in Cambodia. One example is Senator Ly Yong Phat, whose O-Smach Resort has been linked to scam operations.

While police sometimes raid these sites and rescue people (such as in Poipet last year, when 215 foreigners were freed), critics say these actions mostly hit smaller groups, while those with political protection remain untouched.

Cambodia has faced criticism from other countries and pressure from groups like the United States, which has imposed sanctions on people such as Ly Yong Phat. Reports on human trafficking have also downgraded Cambodia’s rating. Still, scam compounds continue to operate in casinos, hotels and special economic zones.

Journalists looking into these scams face harassment and threats, showing how crime and government interests often overlap. Accounts from survivors and UN research confirm that forced labour and abuse are common, while the real organisers rarely face real action.

For more details, you can check the U.S. Treasury sanctions list or reports from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime.