BEIJING – In a twist fit for a spy novel, Dutch chipmaker Nexperia is set to restart shipments from its Chinese sites, easing fears of a supply shock in global car production. The White House confirmed the step late Friday as part of a limited trade thaw with Beijing.

It follows weeks of turmoil that saw the Netherlands take control of the firm, China block exports, and automakers scramble for backup plans. For a sector where humble semiconductors power everything from EVs to kitchen appliances, this looks less like a win and more like a pause in a long-running struggle.

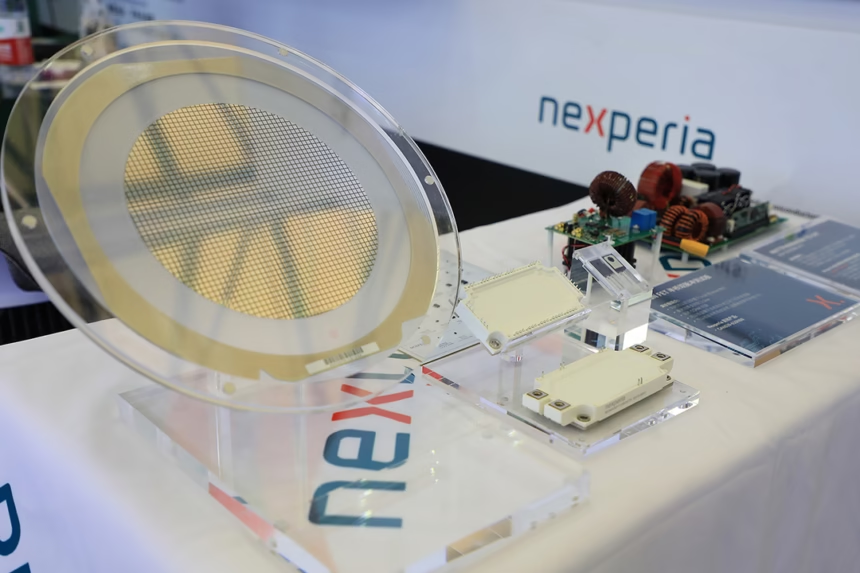

Here is how it unfolded. Nexperia, a major supplier of discrete parts such as diodes and transistors, was bought in 2019 by Wingtech Technology of China. Wingtech has strong links to Beijing’s tech drive. By late September 2025, the Dutch government dusted off an old security law and effectively nationalized Nexperia, citing governance failures and fears that sensitive know-how could flow to China.

Court records later pointed to pressure from Washington, with Wingtech added to a restricted export list during wider US-China tensions. Nexperia’s Chinese chief executive was removed, and operations from Nijmegen to Dongguan slowed to a crawl.

The blowback was immediate. On 4 October, China’s Ministry of Commerce barred exports of Nexperia goods made in China. Those plants handle packaging for around 70 percent of the chips produced in the Netherlands. These are not top-tier AI chips. They are the everyday components that keep cars running, factory gear operating, and consumer devices stable.

Nexperia’s Dongguan site halted

Their reach made the ban risky. Nexperia’s Dongguan site halted all overseas shipments, even to local distributors. It also pushed yuan-only payments for domestic sales to signal independence. The Dutch parent then stopped sending wafers to China and, in a memo to customers, warned it could not stand behind the quality of any parts leaving the subsidiary. The letter cited “potential risks”, which read like a buyer-beware notice.

Automakers, still bruised by the 2021 shortage, raised the alarm fast. ACEA warned of severe production pauses across Europe. Japan’s auto lobby said delivery assurances were falling away for parts suppliers. French group OPmobility said Nexperia’s components are easy to swap in theory, but qualifying new parts takes time.

That is time neither fast-moving EV players nor large groups like Volkswagen can spare. In the United States, where Nexperia chips feed into vehicles, industry gear, and home appliances, the threat of knock-on effects grew. A Detroit executive said teams had gone into war-room mode, comparing it to the COVID crunch, only layered with tariff pressure.

Diplomacy then took centre stage. The shift came on Thursday during talks in South Korea between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping. People with knowledge of the talks said Nexperia featured in a mini trade accord. Washington signalled it would relax some limits on non-sensitive goods if Beijing showed flexibility.

By Saturday, China’s Commerce Ministry released a short note. It said exemptions could be granted for Nexperia shipments to support the security and stability of supply chains at home and abroad. Companies short of parts were told to contact officials. It was a rare nod to practicality over posture.

Politics and the chip supply chain

A White House fact sheet due on Monday is expected to lay out the details. Insiders describe a tight arrangement. Exports resume for auto and industrial uses, with stricter Dutch oversight and US export rules attached.

Nexperia kept quiet, though a spokesperson pointed to ongoing diversification moves, such as seeking packaging partners in Malaysia and Eastern Europe, which started before the dispute. Behind the scenes, the Chinese arm appears to be taking a firm stance.

Staff have been told to follow local guidance over head office instructions, according to people familiar with the situation.

This saga highlights how exposed the chip supply chain is to great power politics. Nexperia is not TSMC, yet before the crisis, it produced about 2.5 billion dollars of goods a year and supplied roughly a tenth of the global market for discrete components.

The restart should buy time. Supply trackers say shipments could pick up by mid-November. The damage still lingers. Wingtech, Nexperia’s former parent, posted a 280 percent jump in third quarter profit last week, but warned of cash flow pressure tied to the dispute, a sign of deeper strain.

Analysts strike a cautious tone. “It is a plaster on a deep wound,” said Dr Lena Voss, a Gartner supply chain expert. “Only broader sourcing can fix this. Lead times are around 20 weeks, so this reprieve feels temporary.” EV startups such as Rivian and Lucid may switch faster to new providers.

Big carmakers face tougher qualification and certification hurdles. The people cost is real as well. Thousands of workers in Dongguan and Nijmegen saw their pay and prospects put at risk, a reminder that chips are not just silicon, but livelihoods shaped by politics.

As Nexperia ramps up its lines, one big unknown remains. Is this closure or a pause before the next round? Trump and Xi are set to meet again at Davos, and the EU is weighing a wider chip policy. A fresh twist could arrive at any moment.

For now, car factories can breathe again. In the odd world of semiconductors, that passes for normal.