CHIANG RAI – Retired schoolteacher Mr. Boonthan Thammapanya has taken a bold step to expose corruption at his former school. After ongoing health issues, including a brain tumour, and seeing little action from authorities, he decided to hang signs outside his home in Sri Wiang Road, Muang District, detailing the wrongdoing he witnessed.

Boonthan, now 62, retired two years ago, but concerns about misconduct in the school stayed with him. After seeking treatment for his illness, he worried he might pass away before the truth came out, so he made his story public.

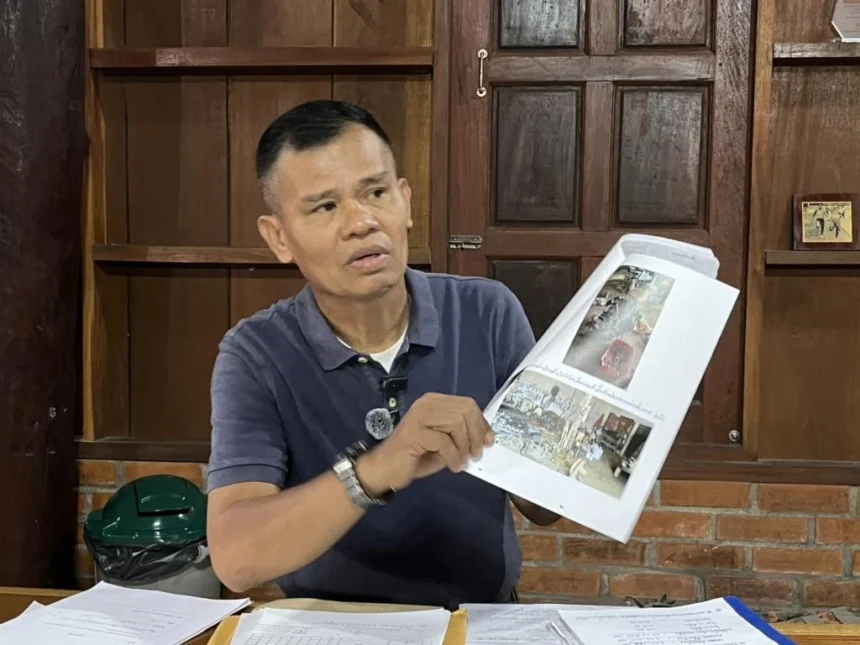

He collected documents and submitted complaints to the National Anti-Corruption Commission, the Public Sector Anti-Corruption Commission, and the Minister of the Interior. Despite these reports, little progress was made, and the school principal in question has already resigned. As a result, Mr. Boonthan felt compelled to make the issue public so that the community would be aware.

He revealed that equipment purchases for the school were made through a car repair shop linked to school management.

Ghost Students

When he checked the listed supplier, he found it had been a repair business for over a decade, with no record of selling school equipment. The village chief confirmed there had never been such a shop in the area.

He also noticed all three shops that bid for the school contracts used the same phone number. In another case, the names of students who no longer attended the school were kept on the rolls so the school could keep collecting per-head government funding. In the 2017 budget, there were 215 “ghost students”, and in 2021, there were 173, totalling 388 fake names and an estimated loss of 1.5 million baht.

In 2021, during the COVID-19 crisis, the government assigned student aid using ID numbers. When the ghost students were exposed, the school quickly removed 173 names to cover it up—but by then, funds had already been claimed.

Near the close of the 2024 budget year, leftover school funds were distributed as cheques to 24 teachers, who were asked to cash them and return the money to the school in cash. Boonthan said he has never seen or heard of such an unusual system anywhere else.

There were also concerns about the misuse of a student savings cooperative fund.

School Cronyism

Boonthan said these cases were only part of a bigger problem. He was worried that this repeated misuse of taxpayer money would continue unchecked. He stressed that all his evidence was genuine and properly sourced, showing a serious issue in the education sector.

He took his documents to Bangkok to report them, and since then, several teachers who misused funds have returned the money or transferred to different schools. Still, official investigations have moved slowly.

He added that, among school staff, there were two groups: those who benefited from corrupt dealings and those who did not. Some teachers consistently earned extra pay and privileges, regardless of their actual contribution.

Meanwhile, others who did exceptional work were denied fair recognition because school leadership redirected rewards to their allies. Boonthan said he could not accept this unfairness.

He recounted warnings from colleagues about personal safety, as exposing these issues could upset former school leaders who gained from the schemes. Boonthan has since filed an official record with Chiang Rai police, confirming he will keep pushing for transparency.

Corruption in Thailand’s education system is a persistent issue, deeply embedded across various levels, from school administration to government oversight, and has been documented in multiple reports.

Funds allocated for school meals, textbooks, supplies, and infrastructure are frequently misappropriated. A 2019 study by Associate Professor Pornamarin Promgrid of Khon Kaen University found that approximately 30% of school budgets for facility upgrades were siphoned off by officials and school directors.