CHIANG RAI – On June 18, 2025, a meeting took place at the Ban Huai Luk Community Hall in Wiang Kaen District, Chiang Rai. The event aimed to present updates and gather feedback on the Pak Beng Hydropower Project, planned for construction on the Mekong River in Laos, about 97 kilometres from the Thai border.

Dr. Worawit Phadungsriboon, Deputy Director of the Pak Beng Power Project, explained that the dam is designed to let water flow in and out at the same rate. He said environmental impacts across borders have been assessed, with plans to store water at two different levels depending on the season.

In the rainy months, water would be kept at 340 metres above sea level, while in the dry months, it would drop to 335 metres. The dam will feature 14 spillway gates, 16 turbines, a navigation channel and fish passageways following recommendations from the Mekong River Commission. Construction is expected to start in October 2025, first on the right bank.

Loan agreements are in place, but require more studies and a fund of 45 million baht for local development, similar to other Mekong projects.

Yaowapa Chuwong from Team Consulting Engineering and Management said the cross-border environmental impact study took years and was submitted to the Lao government. The report aims to stay current and follow Mekong River Commission guidelines. Lao law requires such studies if cross-border impacts are possible.

It predicts possible effects and suggests ways to prevent or reduce them, though the study is not finished. She asked for suggestions to improve the plan.

Yaowapa added that the most important concern is water flow and levels. The project uses international mathematical models to predict water changes, comparing them to the lowest points in eight villages. Results show that, no matter the season or flow, water levels should not reach Chiang Saen or become stagnant.

She noted that Pa Dai Rapids, though a low point, should remain safe. Measures are being taken to lower the water level at the dam, helping maintain activities at Pa Dai and nearby areas, even if it means less electricity is produced.

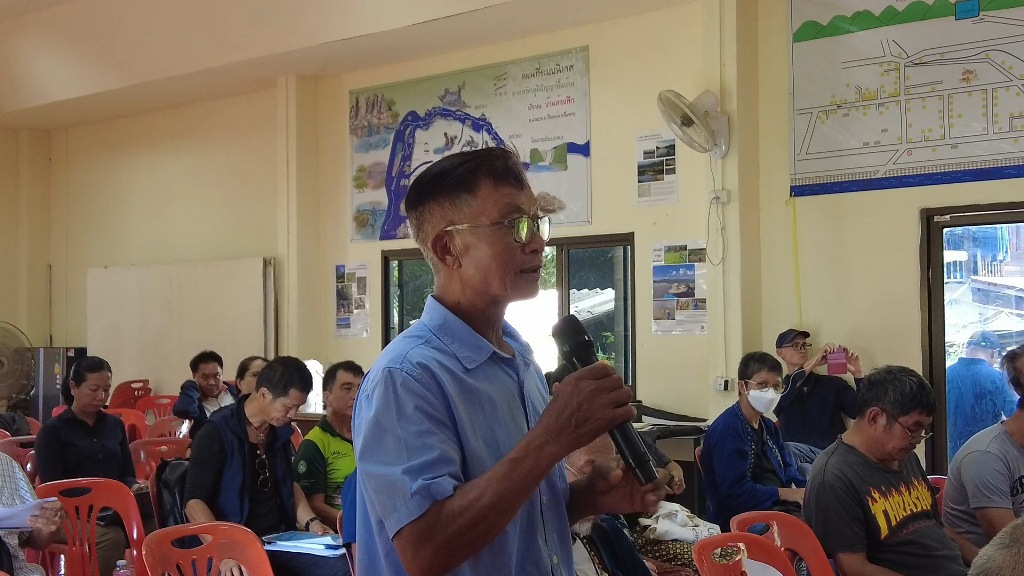

During the public feedback session, Thongsuk Intawong, a former village head from Huai Luk, said locals have worried for years. He said that with the dam about 90 kilometres away, water could flood their homes even with a storage level of 335 metres above sea level.

Past meetings confirmed that damage is likely, and people are not in favour. He voiced concern about who would take responsibility if flooding happened and how people would be relocated. He stressed that villagers, who rely on daily work, do not have the same resources as the project backers.

Chaiwat Duangthida, also from Huai Luk, said his main income comes from fishing, earning several hundred thousand baht a year. He fears the dam will block fish migration and change water flow, making it harder to fish. He pointed out that last year, floods at Pa Dai Rapids reached 357 metres, much higher than the storage level planned.

Compensation from previous floods has not covered all losses, and he doubts the project’s budget will be enough. He also raised issues about unclear borders and fishing rights, which could last decades.

Janya Jantip, from the Mekong Women’s Network, spoke for local women. She worries that if the dam goes ahead, women who fish and farm along the river will lose their jobs and land. She stressed that money is not enough; people want to keep their land and livelihoods.

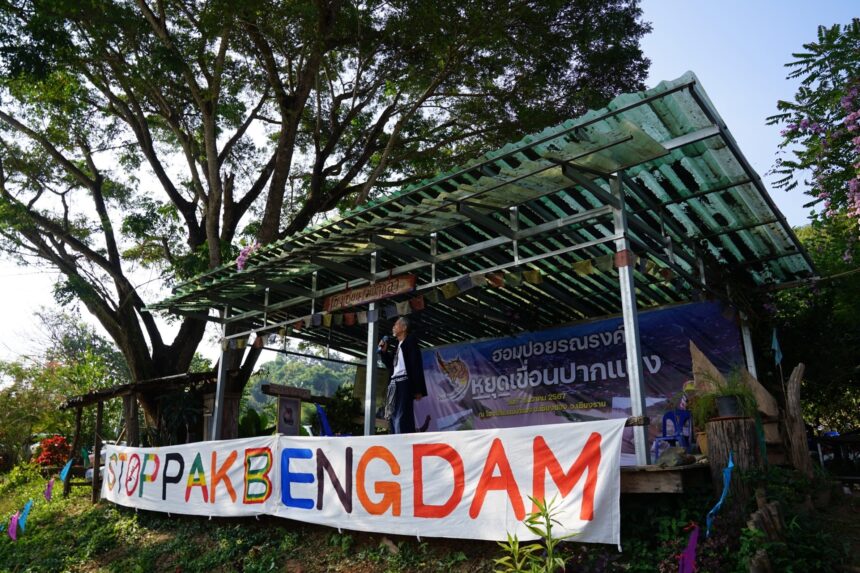

Niwat Roykaew, chair of the Chiang Khong conservation group, said the Pak Beng project has lacked transparency for over ten years. He argued that the public’s concerns have not been answered, yet a 29-year electricity purchase agreement has been signed.

He believes the dam is not being handled properly and that studies are only taking place after contracts are signed. He suspects that the cross-border impact study is only a requirement for loan approval, and does not trust it will address the real problems, such as local flooding and impacts on tributaries.

Piyanun Jitjang from the same group noted that last year’s flood at Pa Dai Rapids happened even without the dam. She fears that a dam could slow the river and cause more flooding in local villages. She also worried that government officials have only shared information with eight villages, and that the information is outdated.

Pianporn Deetes from International Rivers said that mining upstream in China has already led to heavy metal pollution in the Kok and Sai rivers. She warned that even if the company’s figures are correct and flooding does not happen, the Mekong could become polluted with toxic runoff. She doubts the company could handle these new problems if the dam is built.

Pairin Sorsai from the International Rivers Foundation said the recent report was only in English and not fully shared with locals. She encouraged the company to provide better information in Thai, especially regarding water levels. She pointed out that some data being shared is almost twenty years old.

The overall mood at the meeting was tense, with most attendees expressing deep concern about the dam’s potential impact on the Mekong River. Many who attended were elderly, openly discussing their worries about the future of their river and their way of life.