MANILA — Typhoon Ragasa spun up over the Philippine Sea on Sunday, 21 September 2025, forcing tens of thousands from their homes as it swept across the northern parts of the country. With sustained winds at 185 kilometres per hour and gusts reaching 230 kph, Ragasa (locally called Typhoon Nando) has arrived as the most dangerous storm of the season so far.

Local officials have issued urgent evacuation orders in coastal and hillside villages. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. put the country on alert, telling agencies to boost defences in case the storm becomes one of the most destructive in years.

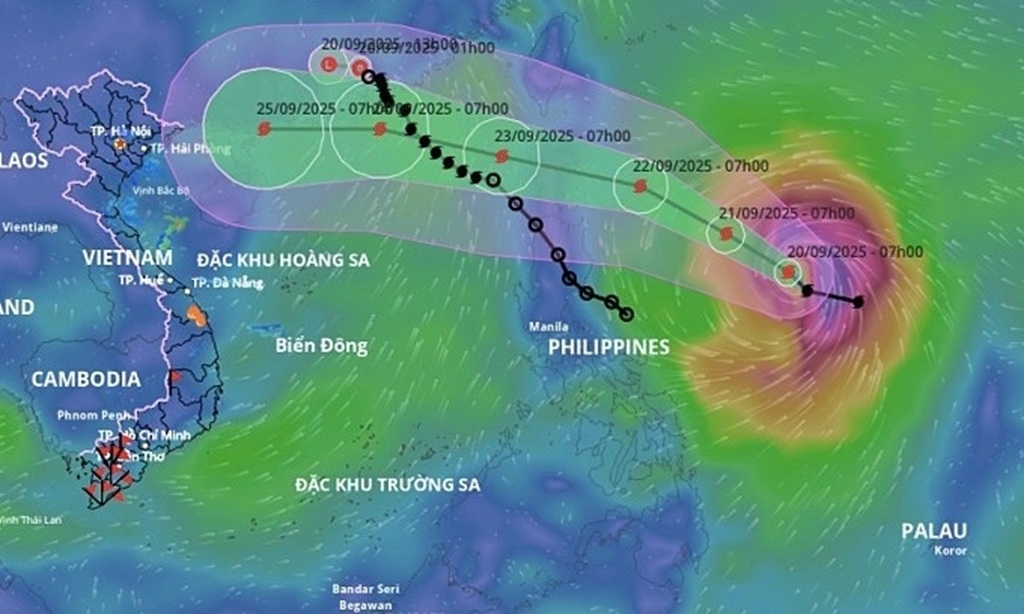

Typhoon Ragasa is the 14th named storm of the 2025 Pacific season. It rapidly developed from a low-pressure area that entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) just days before. By midday Sunday, the typhoon’s centre sat some 485 kilometres east of Aparri in Cagayan province, moving west-northwest at about 15 kph.

Its path threatens the northern edge of Luzon, the country’s crowded main island, and forecasts show it could brush across the Batanes and Babuyan Islands by Tuesday afternoon, 23 September. PAGASA, the Philippines’ weather bureau, raised storm signals as high as Signal No. 4 in parts of Cagayan, Isabela, and Ilocos Norte, signalling winds strong enough to knock down trees, powerlines, and less sturdy homes.

The area threatened by Typhoon Ragasa stretches from the rough northern coastline down to the low-lying farmlands in the south. In Cagayan Valley, where people face the most immediate risk, whole communities in Pamplona and Aparri have been told to leave.

Disaster officials say over 20,000 people have taken shelter in safer buildings by Sunday evening. “The river’s rising fast, and these winds are nothing like we’ve heard before,” said Maria Santos, a 62-year-old rice farmer from Gonzaga, holding a soaked duffel bag outside a school now used as a shelter.

Heavy Rains from Typhoon Ragasa

Heavy rainfall, added to by Typhoon Ragasa’s pull on the southwest monsoon, has dropped up to 200 millimetres in just one day. This has already led to landslides in the Sierra Madre hills and sudden flooding in rice fields.

Central Luzon, with flood-hit provinces like Bulacan and Pampanga, is also watching the skies. Residents are under Signal No. 3 alerts, with strong winds and expected storm surges of up to three metres on the eastern coast of Manila Bay.

In Metro Manila, where 13 million people live in flood-prone areas, emergency workers have set up rubber boats and sandbags, remembering the disaster of Typhoon Ketsana in 2009 that claimed hundreds of lives.

Up north, Batanes—a tiny chain of windswept islands closer to Taiwan than Manila—is expected to get the strongest winds. With just 18,000 people, local leaders have ordered a full coastal evacuation.

Seventy tourists remain stranded after flights were grounded until Wednesday. “We’re getting ready for the worst,” said Batanes Governor Albert Ray Flores during a choppy radio call.

Typhoon Ragasa’s impact on the population is already clear. Weather bulletins predict up to 500 millimetres of rain in some areas within three days, increasing the risk of deadly slides and rivers spilling over.

Farms in Isabela, a key food producer for the country, could lose millions of pesos in crops, pushing up food prices after last year’s harsh dry spell. Health staff warn of possible outbreaks in crowded shelters.

The Philippine Red Cross has sent water treatment units and first aid supplies. President Marcos has pledged emergency funds and sent 5,000 troops to help with rescue work.

Typhoon Ragasa Pushes Northwest

Typhoon Ragasa exploded from a tropical depression into a super typhoon in less than two days. Scientists point to warmer oceans, possibly linked to climate change, as the reason storms grow so fast and fierce. “This is no ordinary storm—it’s the result of our warming planet,” said Dr Lisa Tan, a climate expert at the University of the Philippines.

“We saw something similar with Haiyan in 2013, but Typhoon Ragasa could bring even more danger.” Satellite images show a clear eye surrounded by massive clouds, marking a textbook example of a powerful typhoon.

As Typhoon Ragasa pushes west-northwest, its next targets are the Luzon Strait and Taiwan. In Taiwan, about 300 people have left their homes along Hualien’s coast, and warnings are out for huge waves.

Taiwan’s weather bureau expects the typhoon to skirt its southern coast from Monday to Wednesday as a possible Category 4, with winds over 208 kph.

Predictions show it will likely reach southern China, including Guangdong, by Thursday, 25 September, and could hit Hong Kong with extreme winds and large waves, similar to Typhoon Mangkhut in 2018. Vietnam, further west, could see heavy rain if the storm loses power after crossing into China.

For Thailand, the news is far less threatening. The country sits well south and west of Ragasa’s path. The Thai Meteorological Department says there is no direct effect, as Typhoon Ragasa heads north toward China instead of moving into the Gulf of Thailand.

“Typhoon Ragasa is still far to the east of Luzon, with no impact on our monsoon,” a department spokesperson said. Some stronger rains might hit parts of Bangkok and the Andaman coast, but nothing like the evacuations in Manila. Tour operators in Phuket and Pattaya report no cancellations due to Ragasa.

Back in the Philippines, a mix of resolve and worry fills the air. On Calayan Island, fishermen share old storm tales over instant noodles in the evacuation centre. “Typhoons are nothing new,” said Jose Reyes, an elder fisherman, looking at the sky, “but this one’s different.”

As darkness settles, the nation waits and watches, radar screens lit up with the typhoon’s relentless approach. Ragasa may just pass by Thailand, but for the Philippines, it feels like another test of strength—a reminder that living with typhoons is a way of life marked by wind and water.