LADAKH, India – The clear autumn air in Leh was filled with smoke and anger on Wednesday. A peaceful rally for constitutional guarantees tipped into street clashes, leaving four dead and more than 70 injured in Ladakh.

The local Bharatiya Janata Party office, seen by many as a symbol of broken pledges, was gutted by fire. Protesters, many of them young, pressed for full statehood for Ladakh and inclusion under the Sixth Schedule, promises they say New Delhi has delayed for years.

The unrest broke out around noon during a shutdown called by the Leh Apex Body, a civil society coalition of Buddhist and Muslim groups. Hundreds poured into Leh’s streets, carrying signs that read “Statehood Now” and “Sixth Schedule or Bust”. Students and young professionals led the march towards the BJP office, releasing years of frustration with direct central rule.

Witness accounts painted a sudden surge of violence. “We were asking for our rights when police pushed us back,” said Tashi Dolma, a 22-year-old student. “Tempers snapped. Stones flew. Soon the BJP office was on fire.”

Videos on social media showed thick smoke rising from the single-storey building. Saffron flags curled in the heat while crowds threw stones and set furniture alight. A CRPF vehicle nearby was also torched, its tyres melting on the road as projectiles rained down.

Protest Turned Ugly

Outnumbered security forces fired tear gas and charged with batons. The pushback inflamed the crowd. Doctors at the district hospital reported gunshot injuries and baton wounds. Local sources confirmed at least four deaths, young people caught in a burst of violence that shocked the country.

“Two or three of our youth have sacrificed their lives,” said Leh Apex Body chair Thupstan Tswang, his voice breaking on a phone line from Leh. “We will not let their sacrifice be in vain. The Centre must respond.”

At the heart of the movement stands Sonam Wangchuk, the engineer and climate activist whose 15-day hunger strike rallied more than 500 supporters. His innovations on water storage inspired a generation, and his call for restraint reached audiences across India.

He ended his fast on Wednesday afternoon as the violence crested. In a video message, he expressed sorrow and anger. He said the young crowd ignored pleas and bullets and warned that violence would harm the cause.

He urged an immediate halt to the chaos. His appeal captured the mood of a campaign simmering since 2019, when Ladakh became a Union Territory after the end of Article 370.

Buddhist-Muslim Conflict

Many in Ladakh, split between Buddhist-majority Leh and Shia Muslim-majority Kargil, first welcomed the split from Jammu and Kashmir. They believed it would free them from Srinagar’s neglect.

The BJP, riding high on national promises, offered statehood, Sixth Schedule protections, job reservations, and separate Lok Sabha seats for Leh and Kargil. Six years later, those pledges feel empty to residents.

As a Union Territory, Ladakh answers to a Lieutenant Governor in Delhi. Elected Hill Development Councils have been sidelined on land policy, mining, and hiring. Unemployment sits near 18 percent. Young people watch outsiders take scarce posts while the region still lacks its own Public Service Commission.

The demands are four and simple. Full statehood to restore lawmaking power. The Sixth Schedule status is to protect tribal land and culture, as in parts of the Northeast. A dedicated Public Service Commission to make recruitment fair. Two parliamentary seats to strengthen Ladakh’s voice in Delhi.

“We are not separatists, we are Indians asking for our due,” said Chering Dorjay, former Leh Hill Council chairman and a key figure in the Leh Apex Body. Talks with a Home Ministry panel led by Minister of State Nityanand Rai have inched forward since 2023, with the last meeting in May ending without progress. Another round is set for 6 October, but many here fear it is a stalling move before Hill Council elections.

The crisis is rooted in Ladakh’s geography as much as its politics. This cold desert of around 300,000 people sits at 11,000 feet, facing two contested borders. To the west and north lies the Line of Control with Pakistan, shaped by the 1999 Kargil War and the icy Siachen Glacier.

The Indus River cuts through the region on its way to Pakistan’s heartland, making dams and diversions a sensitive issue under the Indus Waters Treaty.

Ladakh and China

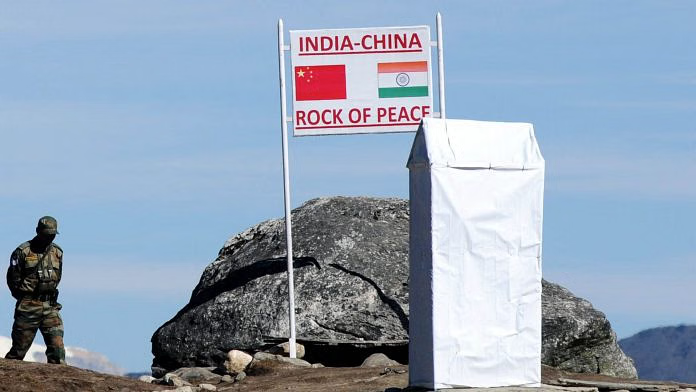

The eastern frontier raises even higher stakes. Along the Line of Actual Control, China holds Aksai Chin, a barren plateau of about 37,000 square kilometres seized after the 1962 war. Beijing’s Xinjiang-Tibet road runs through this area.

For India, Ladakh anchors the approach to that frontier, with the Darbuk-Shyok-DBO road linking troops to advanced posts near Aksai Chin. The 2020 clash in the Galwan Valley, in which 20 Indian soldiers died, showed how quickly tensions can spike in these heights.

Ladakh’s passes, including Khardung La, are more than tourist landmarks. They are choke points in any two-front military plan. China’s moves affect India’s posture in the east. Pakistan’s partnership with Beijing under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor complicates access to Central Asia.

On Siachen, Indian troops endure brutal cold while watching the Shaksgam Valley, which Pakistan handed to China in 1963, a decision India still rejects. In a theatre this sensitive, local turmoil raises alarms. Officials talk of external fishing in troubled waters, even as they avoid public claims.

The Modi government, which redrew Ladakh’s status in 2019, faces a test. The BJP’s local unit blamed the arson on the Congress and accused a Congress councillor of leading the charge. Lieutenant Governor Kavinder Gupta appealed for calm in a recorded message and asked residents to help restore peace.

Jammu and Kashmir’s former chief minister Omar Abdullah said Ladakhis felt misled, arguing that the promise of statehood had turned into a long delay and central control.

Leh now sits under curfew, with the internet blocked and public gatherings stopped. The Ladakh Festival, a bright spot in the tourist calendar, lost its closing day to the unrest. Monks and traders watched from hilltop monasteries and market lanes, fearful for a fragile environment where melting glaciers feed the Indus and livelihoods depend on balance.

For Ladakh, this is more than a march. It is a decisive moment. A trading crossroads of old now stands at a standstill, waiting for a fair deal. Will Delhi meet the demands with clear steps, or let distrust deepen?

As Wangchuk breaks his fast with a cup of butter tea, one thing is plain. The young of Leh will not wait in silence. They want action on statehood, Sixth Schedule protections, fair jobs, and a stronger voice in Parliament, before the mountains echo with grief instead of slogans.