KERALA, India – In monsoon-soaked Kerala, a rare but deadly parasite has emerged as a serious threat. The organism Naegleria fowleri, often called the “brain-eating amoeba,” has led to an urgent health crisis.

This year, officials confirmed 69 cases and 19 deaths traced to an infection called Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM). The outbreak has forced the state’s respected healthcare system to act fast, while communities worry about the environmental changes linked to the growing spread.

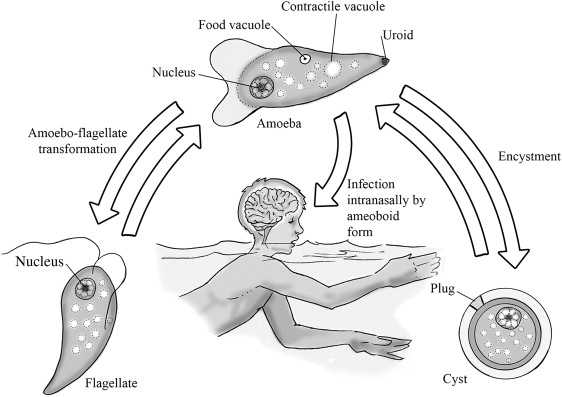

Naegleria fowleri is a tiny, single-celled organism that lives in warm, fresh water. It thrives in ponds, rivers, lakes, and pools that lack proper chlorine, especially when temperatures reach up to 46°C. The amoeba changes form to survive harsh conditions, but its feeding stage (the trophozoite) is most dangerous.

It infects people when water gets into the nose, usually while swimming or bathing. It then travels along nerves to the brain, where it multiplies, destroys brain tissue, and causes severe swelling. PAM has a global death rate between 95 and 98 percent.

Early signs look like other types of meningitis, making it hard to spot at first. Symptoms such as headache, fever, vomiting, and nausea appear in 2 to 15 days after contact, then quickly worsen.

Victims may develop neck stiffness, confusion, seizures, or coma, and many die within 1 to 18 days of symptoms starting. There have only been about 400 cases recorded worldwide since 1965, with past outbreaks rare in India until now.

Rising Numbers in Kerala

Kerala’s first case appeared back in 2016, but the situation escalated in 2024 and 2025. Last year saw 36 cases with nine deaths. This year, numbers have spiked, with 69 confirmed infections across the state and 19 deaths so far.

Victims have included everyone from infants to older adults, and cases have turned up across districts, including Kozhikode, Malappuram, Kannur, and Thiruvananthapuram.

The outbreak has strong links to Kerala’s monsoon-season water sources, which favour the spread of the amoeba. Many cases have come from community ponds, wells, and even household taps. A handful of cases, like a three-month-old baby with no known water exposure, suggest the amoeba may also reach people through contaminated tap water or even during regular practices such as nasal washing.

In Thiruvananthapuram, sniffing water mixed with tobacco powder appears to have caused at least one case.

Experts tie the rise in cases to changing weather patterns. Higher temperatures, heavy rain, and untreated water help the amoeba spread. Dr T.S. Anish from the Kerala One Health Centre highlighted that warmer weather is helping Naegleria fowleri become more widespread. Water quality issues and pollution make things worse, turning even familiar water sources into risks.

How People are Getting Sick

Most infections start when people swim, dive, or bathe in water where the amoeba lives. Young people and children are often at risk since they are more likely to play in water and may have thinner bones between the nose and the brain.

The amoeba does not spread by drinking contaminated water or from person to person. However, some recent cases may involve less obvious routes, such as washing the nose with tainted water or with water used at home.

Authorities uncovered the amoeba in a Kozhikode well used for drinking, and a teenager in Malappuram died after swimming in a pond. These stories show that the risk increases during the rains when ponds and wells fill with fresh but potentially untreated water.

The local government, led by Health Minister Veena George, has acted quickly. A campaign called “Water is Life” focuses on cleaning and chlorinating wells, tanks, and public bathing spots, since chlorine treatment can kill the amoeba. Posters and public messages promote using nose clips, avoiding unsafe water, and keeping stored water clean.

Kerala’s main laboratory now offers quick molecular tests, so samples no longer need to be sent away, saving precious time. Doctors across the state are encouraged to consider PAM in patients with meningitis and recent water exposure.

If caught early, a mix of drugs (including amphotericin B, miltefosine, and azithromycin) can help, and Kerala’s survival rate now stands at 24 to 26 percent, much higher than the worldwide average. This approach saved 14-year-old Afnan Jasim in 2024, now recognized as India’s first survivor of PAM.

New guidelines and rapid response plans have made Kerala the first Indian state with formal protocols to manage these infections. National and local teams are working together to track sources, monitor new cases, and study outbreaks. However, not all cases have a clear source, which can make monitoring harder.

Where the Challenges Lie

Kerala faces hurdles in tackling this outbreak. The infection moves quickly, and symptoms look much like more common diseases. There is no vaccine, and medicines may not always work. Researchers are studying new treatments, but these are still early days.

Public knowledge about the disease is still low. Doctors and volunteers are working to get the message out, saying that simple steps like pinching the nose when swimming or using safe water for nasal cleaning can prevent infections.

The outbreak hints at bigger changes. Climate shifts and inconsistent rainfall affect water safety, creating new threats for public health. Kerala’s advanced health system has helped find and treat cases quickly, but more teamwork is needed, bringing together doctors, scientists, and environmental experts.

Kerala’s safest path forward involves better awareness, safe water practices, and careful monitoring. People should steer clear of untreated water, especially during the rainy season, and use simple protective steps.

The state must keep funding diagnostics, treatment, and outreach so that everyone knows the risks. As the rainy weather continues, Kerala faces hard choices, needing to manage not only this rare parasite but also the wider changes in environment and water safety.