CHIANG RAI – The Hong Hian Mae Nam Khong Local Knowledge Centre in Chiang Khong District, Chiang Rai, locals, academics, students, and locals gathered for a special event. They joined a hands-on activity called “Arsenic Detectives” and took part in a campaign titled “Letters to the Leaders”. The day also included training on basic environmental science and water quality.

The group included Mr. Niwat Roykaew, known as “Teacher Tee”, chair of the Rak Chiang Khong Group, Phra Maha Nikom Mahaphinikkhammo, deputy abbot of Wat Thaton, Dr. Sathian Chantha, an environmental scholar from Chiang Rai Rajabhat University, lecturers from the School of Chemistry at Mae Fah Luang University, community leaders, representatives from Ban Sop Kok, along with local youth and students.

Eight months of water testing reveal a silent crisis

The event opened with a presentation by the youth and project team. They shared results from eight months of continuous water monitoring between May and December 2025.

The data showed that four key rivers that flow through the area, the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and Mekong Rivers, are in serious trouble. Tests found contamination from chemicals, especially arsenic and other heavy metals. The main sources are mining operations and industrial development in neighbouring countries at the headwaters.

Dr. Sathian Chantha, lecturer in Natural Resource and Environmental Management at the Faculty of Science and Technology, Chiang Rai Rajabhat University, explained that these rivers are not just water sources. They are the lifeblood of people in Chiang Rai and along the Mekong.

He said that arsenic levels have reached a worrying point. The danger lies in the fact that arsenic does not always cause instant symptoms. It acts like a “silent killer”. Early exposure can cause rashes and skin irritation. When the body takes in arsenic over many years, it attacks at the cellular level and can harm several organs.

Arsenic is a confirmed carcinogen. If people are exposed to it for 5 to 10 years, their risk of developing cancer rises sharply. He stressed that the food chain is the most serious concern.

When farmers use polluted water in rice fields, the rice plants absorb arsenic very effectively. The toxin then builds up in the grains of rice. When people eat that rice, the poison enters their bodies. In simple terms, the contamination travels from the mine, into the river, into the rice plant, and then ends up on our dinner plates.

“This is no longer a distant issue. It has become a crisis for food security and public health that is creeping towards us quietly,” Dr. Sathian said.

Like watching my own mother on life support

Phra Maha Nikom shared his personal feelings about the Kok River.

“I have bathed in the Kok River since I was in my mother’s womb. This river is life, like blood flowing in our veins. But now, when I stand and look at the Kok River, my feelings are different. It is like watching my own mother lying critically ill in a glass ICU room. I know that there are toxins in her blood, I know she is close to death. We know how to treat her, but we cannot reach her, because the cause of the illness lies beyond our control, in the actions of our neighbours and forces larger than us.”

The deputy abbot of Wat Thaton said that nature is life itself. He was glad to see so many children and young people at the gathering, ready to carry the work forward.

“If no one continues this effort, in 30 years we may not have a river left to look at. We might sit and cry for a dead river, and for our own bodies filled with disease. The problem may seem huge, caused by mining and development in Myanmar, in China, and by policies far away. But if we learn together, stay united, and use wisdom and peaceful methods, heavy problems can become lighter, and what seems impossible can open a path.”

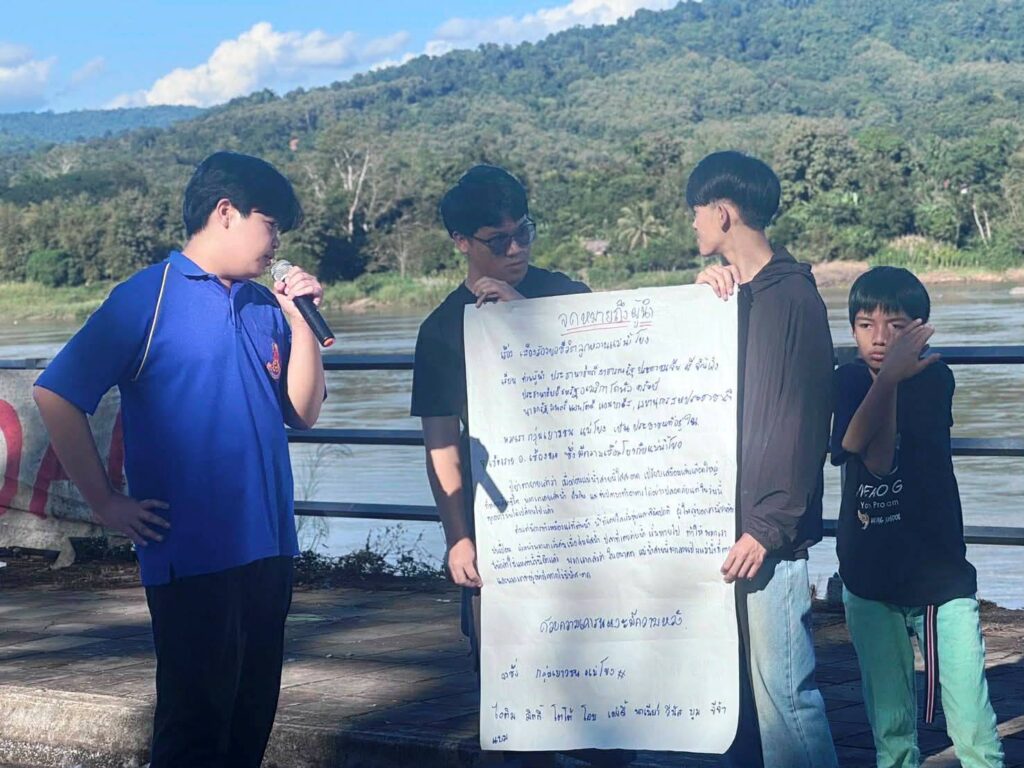

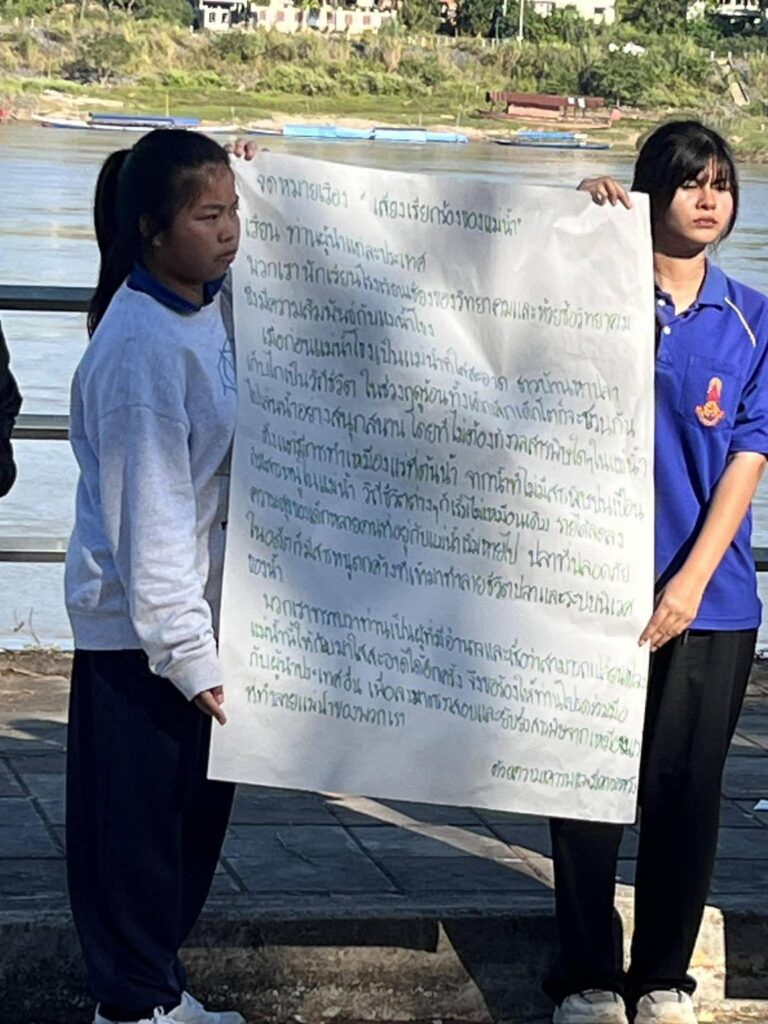

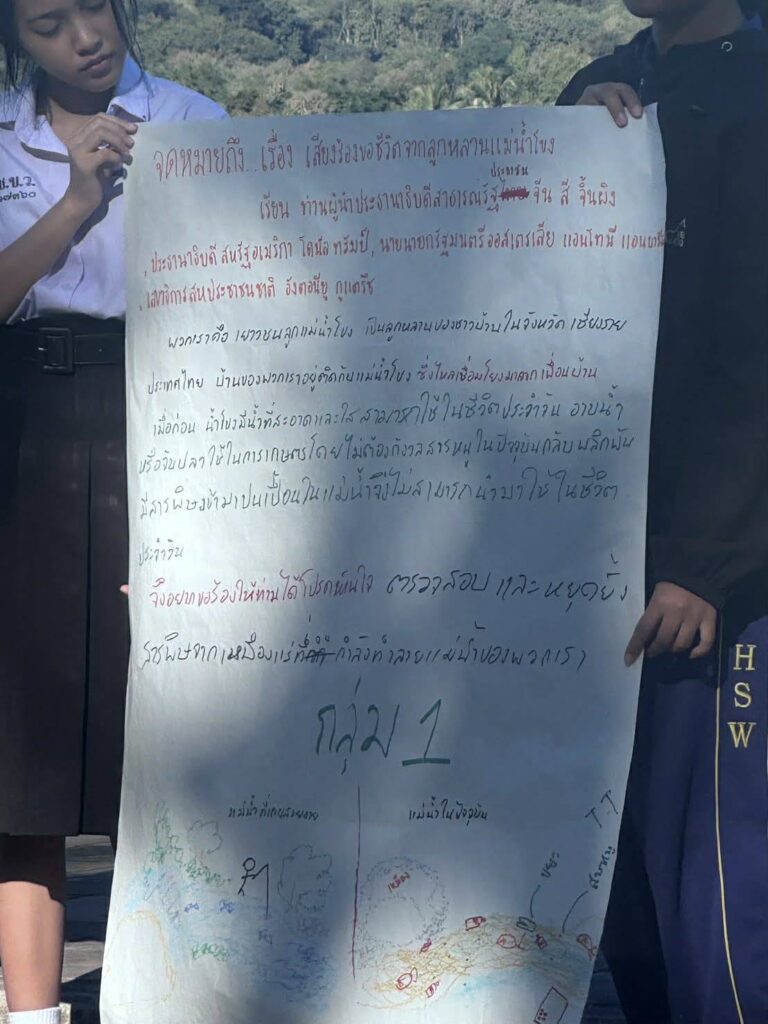

Afternoon session: Letters to those in power

In the afternoon, the youth and villagers sat down to write letters to national and international leaders. Student representatives worked together to draft an open letter that said:

“To the leaders who hold power,

We are a group of young people, children of the Mekong River. We are ordinary citizens in Chiang Rai whose lives are deeply tied to these waters. Our grandparents told us that in the past, this river was clear and clean, like a great artery feeding every form of life. We used to jump in to swim, drink the water, and catch fish to eat safely and happily.

Today, everything has changed. Since mining began upstream, the clear water has turned cloudy. The colour of the river has changed in a frightening way. Adults tell us that toxic substances are now in the water. The fish that once swam in large numbers are disappearing. We no longer dare to even touch the river.

We are afraid. Afraid that in the future, this river will become a ‘dead river’ forever. If that day comes, how will we survive without clean water?

With respect and hope, we share these facts from our hearts. The situation has gone far beyond what local villagers like us can handle alone. We ask you to listen, and to work with others to protect this river that is the breath and life of everyone, before it is too late.”

The children and youth then wrote out individual letters in their own handwriting, placed them in envelopes, and prepared them for delivery.

“This is a declaration that people of the Mekong Basin will not surrender to fate,” said Niwat Roykaew.

“They choose to walk with knowledge, use truth as their shield, and the pure voices of children as their tool for negotiation with the world. From tiny drops of water in the test tubes of the ‘arsenic detectives’, to 3,000 letters about to cross borders, this is the loudest warning that the killing of rivers must stop. Only then can the beauty of the past remain, and the next generations still have clean rivers to sustain their lives.”

Citizen science in the hands of local people

Teacher Tee said that fighting cross-border pollution can no longer depend only on anger or the old style of protest. The “Arsenic Detectives” activity has a deeper purpose, which is to build “citizen science”.

“We want children, youth, and villagers to become researchers themselves. They learn to observe, ask questions, test water quality, collect data, and turn those facts into shared knowledge. When villagers have data in their hands, that data becomes their strongest weapon.”

He explained that this approach is part of a broader strategy that connects “three generations” so that the past, present, and future work together.

The older generation (the past) holds memories. They remember what a healthy river looked like, how plentiful the fish once were, and how people could drink straight from the river. Their stories become a reference point, so younger people can see that the current state of the river is not normal.

The middle generation (the present) includes community leaders, activists, and local workers. They are dealing with governments and companies, holding meetings, negotiating, and trying to prevent the situation from getting worse.

3,000 letters as a living record

The younger generation (the future) includes students and young people who joined the “arsenic detective” activities. They are the ones who will live with the long-term impacts and who will carry the work ahead.

“We are not teaching kids to only complain or shout in anger. We teach them to fight with wisdom, logic, and scientific proof they have helped to gather. This lifts the struggle from a purely local issue to one that reaches the Mekong sub-region and the global stage. It brings elders, who represent the past, together with youth, who represent the future, to tackle the problems of the present,” Niwat said.

Niwat added that the goal is to collect 3,000 letters to send directly to leaders of countries in the Mekong region and to world leaders.

“These are not just ordinary complaint letters. They are a living record from people who are directly affected. They help leaders at every level understand the threat now hanging over the Mekong and its people.”

Each letter, written by a child or community member, carries a personal message. Together, they tell a shared story of rivers in crisis, of communities that refuse to stay silent, and of a region that still believes its rivers can heal if the world chooses to act.