CHIANG RAI – The River for Life Association and the Chiang Rai Community Rights Network, representing ethnic communities in Mae Yao, have come out against the proposed “sediment-trap weirs” on the Mae Kok River. They are urging the government to engage with Myanmar and tackle pollution at its source.

A community forum took place in Mae Yao Subdistrict, Mueang District, Chiang Rai, to prepare proposals ahead of a public hearing on water quality in the Mae Kok and Mae Sai rivers. The hearing, hosted by the Department of Water Resources, is scheduled for 11 November 2568 at the Chiang Rai Provincial Administrative Organisation hall.

Residents in Mae Yao say toxic contamination in the Mae Kok River has hurt their lives for years. Daily routines, tourism, farming, and fisheries have all suffered. Many can no longer rely on a river that once supported their way of life. Locals say the problem has spanned two governments without any concrete fix.

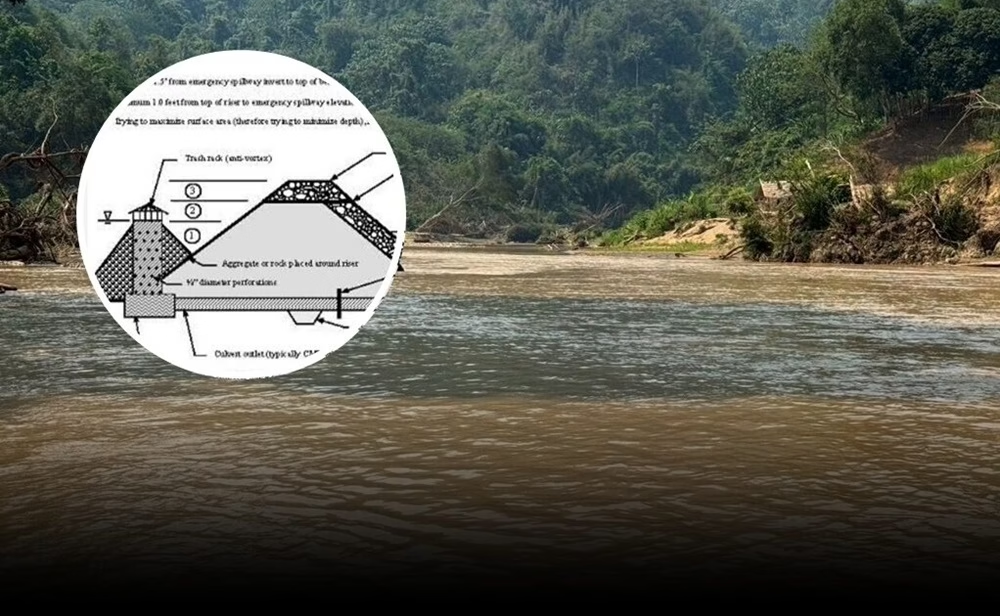

More than 60 residents joined the forum. They shared impacts, drafted proposals, and prepared to submit them to government agencies at the hearing. Their key demands are clear: take urgent action to address toxic pollution and drop the sediment-trap weir project. Locals argue the plan misses the point and cannot remove toxins. Community representatives repeated a firm stance against the weirs.

Wuttipong Sanguanchot, President of the Lahu Association and a representative of communities along the Mae Kok, said people have no faith that the weirs will solve anything. The Mae Kok carries a massive volume of water.

Weirs catch sediment, not toxins. He called on the government to show good faith by engaging Myanmar and using regional forums to address pollution at its source.

Residents also compared the weir plan to treating symptoms, not causes. They questioned the Department of Water Resources’ revised plan to build four weirs in Tha Ton and Mae Na Wang, Mae Ai District, Chiang Mai, with a 173 million baht budget, reduced from an earlier plan for ten weirs.

They say authorities made decisions for communities and kept details from the public. People were left in the dark while the project moved ahead, even though the core issue, toxic contamination, remains unsolved.

Nopparat, a representative of the Chiang Rai Boat Tourism Club, joined communities in Mae Ai in opposing the weirs. He outlined serious impacts on local jobs. The club once had more than 300 boats registered with the Marine Department. In 2567, tourism collapsed. Today, fewer than 60 boats remain.

He added that the government has overlooked people. Real solutions need real commitment. If people matter, fix their problems. Instead, we have been ignored. The forum wrapped up with a set of community-led proposals based on real impacts, ready to present to the Department of Water Resources at the upcoming public hearing.

Although the agenda shifted from the weir project to broader water quality issues, communities in both provinces are united. They reject the sediment-trap weirs and are prepared to mobilize for decisive action from the government.

Mae Kok River Contamination

The Mae Kok River, which rises in Myanmar’s Shan State and feeds the Mekong, flows into northern Thailand through Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai. It has become a tragic channel for severe heavy metal pollution linked to unregulated mining, much of it run by Chinese companies.

Since early 2025, arsenic levels have surged, often up to four times above WHO guidelines. Mercury, lead, cadmium, manganese, and cyanide have also tainted the water, sediment, and floodplains. Fish and shellfish are unsafe to eat, and people in districts such as Mae Ai and Tha Ton report persistent skin rashes, higher neurological risks, and possible cancers.

The contamination stems from open-pit extraction of gold, rare earths, and manganese. Wastewater loaded with chemicals is released untreated into upstream streams, then carried across the border. These toxins have reached crops and drinking water for about 1.2 million people in Thailand, and spread into the wider Mekong basin. The fallout includes worse flooding and more than $40 million in losses across fishing, farming, and tourism.

Thousands of residents have staged protests, while officials have appealed to Myanmar’s junta, the United Wa State Army, and China. Companies skirt domestic environmental limits by operating in conflict-hit frontier zones with little oversight. Cross-border enforcement is urgent, yet measures like silt curtains and routine monitoring only offer short-term relief from a worsening ecological disaster.