CHIANG RAI – Rice farms sit at the heart of Thai life. It fills plates, pays school fees, and shapes village festivals. Millions of smallholders rely on Thai Rice Farms for food, income, and identity. Climate change is shaking that foundation. Rains arrive late or all at once. Heat waves scorch young plants. Floods drown fields that once produced reliable harvests. These shifts threaten both local livelihoods and global rice supplies.

In response, AI-supported farming is starting to act as a new kind of helper. It uses data, weather forecasts, satellite images, and field sensors to give farmers clear advice in simple language. Importantly, these tools are being tested in real paddies in Thailand, in projects backed by Thai agencies and international partners, not just in research centres.

This article looks at how Thai Rice Farms use AI day by day, how it helps protect harvests, raise incomes, cut emissions, and what challenges still stand in the way.

Why Thai Rice Farms Need AI To Survive Climate Change

Thai Rice Farms sit on the front line of climate change. Most rice is grown outdoors, in low-lying plains and river basins, so farmers feel every shift in rain and temperature.

Over recent decades, Thailand has warmed by around 0.09 to 0.18 degrees Celsius per decade. At the same time, rainfall has become more unpredictable. Some years, the monsoon arrives months late. In others, storms dump huge amounts of water in a few days.

For farmers, this means constant stress:

- Young seedlings die when rain does not arrive on time.

- Heavy rain close to harvest ruins grain quality.

- Extreme heat damages flowers and grains, sometimes cutting yields by half.

Flooded paddies also release methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. Thailand is among the largest rice-related methane emitters in the world, so there is strong pressure to cut emissions from rice fields through better water and fertiliser management.

In the past, farmers relied on memory and local signs to plan their season. These methods worked when the climate was stable. Today, patterns are shifting too fast. Farmers need tools that can read thousands of data points and spot new trends.

This is where AI comes in. AI can sift through weather forecasts, soil moisture readings, and satellite data, then translate them into simple advice: when to plant, when to irrigate, when to watch for pests. It does not replace farmer knowledge. It extends it.

Climate threats that put Thai Rice Farms at risk

Climate change hits Thai Rice Farms from several directions at once. Four threats stand out.

1. Too much water: floods and intense rain

More frequent heavy storms mean that low-lying fields near rivers flood more often. When paddies stay under water for more than a week, the rice plants often die. Even short floods can wash away fertiliser, flatten crops, and make it hard to use machines. Grain that ripens in wet conditions can sprout or rot, which forces farmers to accept a lower price.

2. Too little water: droughts and delayed monsoon

In recent years, the rainy season has started months later than usual. Farmers who planted early lost seedlings because the soil stayed dry. Others waited to plant, then had a shorter growing season and smaller harvests. In non‑irrigated areas, many farmers can grow rice only once a year, so one failed season means a year without income.

3. Rising temperatures

Higher average temperatures and more hot days put stress on rice plants. When heat strikes during flowering, grains do not form properly, and yields fall. Heat also encourages fungal diseases that damage leaves and panicles. In some parts of Thailand, farmers have already seen yield drops of up to 50 percent in bad heat years.

4. More pests and diseases

Warmer and wetter conditions are ideal for insects and diseases. Pests that once appeared only once a season can now show up twice. Outbreaks of brown planthopper or leaf blight can move quickly across a district. Without early warning, farmers often spray large amounts of pesticides, which raises costs and harms the environment.

Each threat on its own is hard enough. Together, they make rice farming feel like a gamble.

Limits of traditional farming knowledge in a shifting climate

Older farmers in Thailand often read the sky and the behaviour of birds or insects to guess wherains will arrive. They remember seasons from decades ago and plan their work accordingly.

These skills are still valuable, but the climate has shifted. Rains that used to arrive in April may now start in July. A village that rarely saw floods might get hit twice in five years. Local signs alone no longer give a clear guide.

Smallholder farmers are especially exposed. Many have small plots, little savings, and no formal crop insurance. A single failed harvest can push a family into debt or force them to send young people to cities for work.

AI tools offer a way to support this traditional knowledge with fresh, objective data. Instead of replacing farmer wisdom, they act like an extra pair of sharp eyes, constantly watching weather charts, river levels, and satellite images, then turning that information into simple suggestions that farmers can check against their own experience.

How AI Tools Work On Thai Rice Farms Day To Day

AI can sound abstract, yet on Thai Rice Farms it often shows up in very practical ways: a text message on a basic smartphone, a map on a tablet at the local cooperative, or a printed advisory sheet prepared by an extension officer.

Across Thailand, large projects supported by Thai agencies, UNDP, IRRI, and the Green Climate Fund are rolling out AI‑based tools. Some focus on water management, others on crop planning and pest alerts. Many of these efforts are described in detail in UNDP’s story on climate action in Thailand’s “Rice Bowl” region.

At the core, the idea is simple: AI pulls together data from weather stations, satellites, soil sensors, and farmer records, then uses models to suggest what to do, and when.

AI weather and crop advice apps that guide farmers every week

One of the most visible tools is the AI‑supported advisory app. Farmers register their field location, rice variety, and planting date. The system then combines weather forecasts, soil moisture information, and crop growth models.

In return, farmers receive clear messages such as:

- Best week to plant, based on expected rains.

- Days when they should irrigate or hold back water.

- Warnings about high risk of pests or disease in the coming week.

Many platforms use colour‑coded alerts, for example, green for low risk, yellow for caution, and red for high risk. Some share simple maps that show which villages face flood or drought risk in the next ten days. Farmers access this advice through smartphones or through local extension officers who print or explain the messages.

These apps are part of climate‑smart rice programmes backed by groups like UNDP and IRRI. They help farmers adjust plans in real time, rather than waiting for information that might arrive too late.

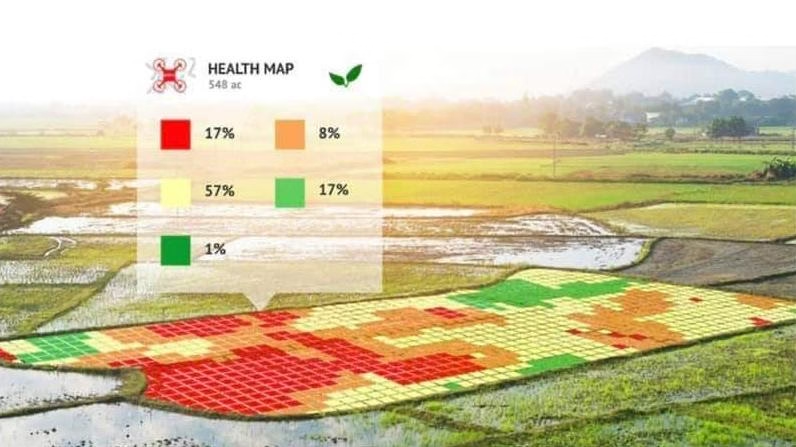

Drones and AI-powered images that reveal crop health problems early

In several provinces, farmer groups now hire drone service providers to scan large rice areas from the air. The drones capture detailed images in visible and infrared light.

AI systems then study these images to spot patterns that human eyes might miss:

- Patches where plants are yellowing, a sign of nitrogen shortage.

- Sections of the field that are too dry or too wet.

- Early signs of pest damage or disease.

With this information, farmers can treat only the affected parts of the field instead of spraying everything. This saves money on fertiliser and chemicals, reduces pollution, and protects beneficial insects.

Local entrepreneurs often run these drone services. They visit several villages, process images using AI tools, then return with simple maps and explanations that farmers can discuss in groups.

The approach matches the goals of projects led by the International Rice Research Institute, which focus on using digital platforms and drones to strengthen rice farming in Thailand.

Smart water management: AI supports Alternate Wetting and Drying

Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD) is a water‑saving method that suits many Thai Rice Farms. Instead of keeping paddies flooded all the time, farmers let the water level drop to a set point, then irrigate again.

AI tools make AWD easier to manage. Sensors or simple water tubes in the field track how deep the water is. AI combines this with weather forecasts and crop stage to suggest when to drain and when to refill.

In practice, a farmer might receive a message saying:

- “Water level will reach safe lower limit in two days, prepare to irrigate then.”

Studies and pilot projects show that AWD can cut methane emissions sharply and save around 30 percent of irrigation water while keeping yields stable. In some river basin schemes, AI‑supported scheduling also helps whole villages agree on shared irrigation turns and operate community floodgates in a fair and timely way.

Matching climate-resilient rice varieties with local fields using AI

Breeders have developed rice varieties that handle floods, droughts, or heat better than older types. The challenge is to match each variety to the right field.

AI and digital tools help by combining maps, climate records, soil data, and farmer feedback. A system can flag low‑lying plots that flood often and suggest flood‑tolerant varieties, while recommending drought‑tolerant types for upland fields with poor rainfall.

One famous example from Asia is Swarna-Sub1, a rice variety that can survive being underwater for longer periods. In fields where floods now occur more often, such varieties can make the difference between a lost crop and a decent harvest.

By connecting variety databases with local field data, AI helps extension officers give targeted advice instead of one-size-fits-all messages.

Real Benefits For Farmers: Higher Yields, Lower Risks, Stronger Incomes

For farmers and policymakers, the key question is simple. Do these tools help real people on real Thai Rice Farms?

Evidence from climate‑smart rice projects in Thailand suggests they do. Farmers using improved methods, supported by data tools, have seen yield increases of around 10 to 15 percent. At the same time, they have cut input costs by about 10 to 20 percent in some areas, thanks to more accurate use of water, fertiliser, and chemicals.

Rice projects across Asia show similar patterns, as outlined in this broader review of climate‑resilient and sustainable rice farming.

Environmental gains also matter. Better water control and fertiliser timing can significantly reduce methane and other greenhouse gas emissions, which supports Thailand’s climate goals.

More stable yields and better grain quality in a risky climate

AI tools help farmers choose planting dates that fit the likely rain pattern, avoid peak flood periods, and manage water during sensitive growth stages. This reduces the chance of total crop failure, even when the weather is unstable.

In villages where some farmers use AI‑supported advice and others do not, it is common to see smaller yield losses on the supported fields after a bad season. Instead of losing half the crop, they may maintain close to normal yields.

Better timing of fertiliser and irrigation also improves grain quality. Rice that fills well and dries at the right time tends to fetch a better price. Over time, this quality premium can be as important as yield gains.

Cutting costs for water, fertiliser, and chemicals

Fertiliser and pesticides are some of the biggest costs for Thai Rice Farms. When farmers apply them based on guesswork, they often use too much or apply them at the wrong time.

AI‑based recommendations guide farmers to use the right amount, in the right place, at the right moment. This avoids waste and protects soil health. Where AWD and smart irrigation advice are in place, farmers also save on pumping costs and fuel or electricity.

When input costs fall by 10 to 20 percent and yields stay stable or rise slightly, net income improves even if rice prices are flat or falling.

Lower greenhouse gas emissions and cleaner local environments

Rice paddies that stay flooded all year release high levels of methane. By switching to AWD and adjusting fertiliser use, farmers can cut emissions sharply while still producing good harvests.

Some projects in Thailand report methane cuts of up to 30 to 80 percent when AWD is combined with other practices, such as better straw management. These kinds of results are echoed in international discussions on greener rice in Thailand and strong methane reductions from AWD.

Using fewer chemical inputs also protects canals, rivers, and soils from pollution. In some areas, projects encourage farmers to recycle rice straw as animal feed, mushrooms, or building materials instead of burning it, which cuts smoke and carbon dioxide emissions.

These environmental benefits support Thailand’s broader green growth plans and help keep Thai rice attractive in export markets that care about climate footprints.

Support Behind The Scenes: Thai Government And Partners Push AI For Rice

The spread of AI across Thai Rice Farms does not happen by accident. It depends on policy support, finance, and local training.

From 2024 to 2028, several large programmes backed by the Thai government, GIZ, BAAC, UNDP, IRRI, and the Green Climate Fund are working together. They invest in digital platforms, drone services, water infrastructure, and farmer training.

These partners help to:

- Train extension officers and “digital champions” in villages.

- Support local entrepreneurs who run drone and data services.

- Develop climate‑friendly loan products for farmers.

- Upgrade irrigation canals, floodgates, and storage systems.

Without this support, many farmers would find AI tools too expensive or too complex to use.

Large-scale climate-smart rice projects across Thai provinces

National projects aim to reach hundreds of thousands of rice farmers in more than 20 provinces. They often focus on key river basins where climate risks are high, such as low‑lying delta areas and drought‑prone inland plains.

In a typical province, the programme might set up:

- Demonstration plots that compare traditional and AI‑supported practices.

- Farmer field schools, where participants learn how to use apps and simple sensors.

- Community meetings to discuss water sharing and AWD schedules.

Farmers can see real fields, talk to neighbours who are testing the tools, and decide if the methods fit their own farms.

Climate-friendly finance and market rewards for smart farmers

Banks like the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives (BAAC) and other partners are testing climate‑friendly finance. One idea is to offer loans with slightly lower interest rates to farmers who adopt verified climate‑smart practices, including AI‑supported AWD and methane reduction.

Retailers and exporters are also starting to look for climate‑smart rice that meets new standards, such as Thailand’s rice sustainability standard. Some value chains may pay a small premium for rice that comes with lower emissions and strong traceability.

For an 8th‑grade reader, the message is simple. Farmers who protect the climate and use smart tools are more likely to get fair loans and better market access.

Training, digital skills, and farmer-led innovation

New tools only help if people know how to use them and trust their advice. Training and trust-building are central.

In many villages, extension officers and younger farmers act as trainers. They sit with older farmers, show them how to read a simple dashboard, open an app, or understand a traffic‑light risk map. When connectivity is poor, they may download the data once in town, then share the advice offline with neighbours.

Farmers give feedback about which messages are confusing, what language works best, and which features they actually use. Developers then adjust the tools. This two-way flow keeps innovation grounded.

Growing digital skills in rural areas also creates new jobs. Young people can work as drone pilots, sensor technicians, or data interpreters while still living in their home communities.

Challenges And Next Steps For AI On Thai Rice Farms

Even with strong support, there are still hurdles to wider AI adoption on Thai Rice Farms. The goal is to face these challenges honestly while keeping a hopeful outlook.

Key issues include the cost of devices, patchy internet, trust in new tools, fair access for smallholders, and clear rules on data use.

Access gaps: cost, connectivity, and language barriers

Not every farmer in Thailand owns a smartphone. In somehouseholdss there is just one phone shared by several family members. Mobile coverage can be weak in remote areas or inside paddy basins.

Many AI tools are first built in English, or Central Thai Farmers who speak local languages or dialects may struggle with menus or messages that feel too formal or technical.

These barriers can make AI seem far away from daily life. Simple solutions can help:

- Apps that work partly offline and sync when there is a signal.

- Interfaces in local languages, with icons and colour codes rather than long text.

- Community hubs or cooperatives with shared tablets and support staff.

If projects invest in these features from the start, more farmers will feel confident to try the tools.

Trust, data ownership, and fair benefits for smallholders

Data is a sensitive topic. AI tools often collect field locations, yield records, and management details. Farmers may worry about who owns this data and how it might be used.

Clear rules and transparent agreements are needed. Farmers should keep control over their data and understand who can see it. If the data helps generate financial benefits, such as carbon credits for lower methane emissions, farmers should receive a fair share.

Strong farmer organisations and co‑operatives can help members negotiate good terms with tech providers, banks, and buyers.

Scaling up AI in a way that supports people and the planet

As AI use grows, Thailand faces an important choice. Will these tools support inclusive development, or will they mainly benefit big farms?

To support both people and the environment, several steps are important:

- Public investment in rural internet and digital infrastructure.

- Open, trusted data platforms that farmers and researchers can access.

- Long‑term partnerships between government, research bodies, private firms, and communities.

- Continuous farmer education, not just one‑off training.

AI should support farmer judgment, not replace it. When combined with local knowledge and strong community organisations, it can help protect land and water, keep rural communities strong, and maintain Thailand’s role as a leading rice exporter in a warming world.

Conclusion: A Smarter Future For Thai Rice Farms

Thai Rice Farms feed families at home and millions of people abroad. Climate change threatens this role through harsher floods, longer droughts, higher temperatures, and more pests.

AI does not solve every problem, but it offers practical help: better climate risk forecasts, smarter water and fertiliser use, more stable yields and incomes, and lower greenhouse gas emissions. Projects across Thailand already show real progress, with higher yields, lower costs, and cleaner fields.

The next step is to spread these benefits to all smallholders, not just pilot sites. That means fair finance, strong farmer groups, good internet, and clear rules on data and carbon markets.

If Thailand gets AI‑supported climate‑smart rice right, it can protect farmer livelihoods, keep its people fed, and share hard‑won lessons with other rice‑growing countries in Asia. Readers in policy, NGOs, and agribusiness can help by treating AI as a tool for fairness and climate stability, not only for profit.