LOS ANGELES – Jane Goodall, the British primatologist whose fieldwork transformed how people see chimpanzees, died yesterday, aged 91. She passed away from natural causes while on a speaking tour in California, according to the Jane Goodall Institute. Her death closes a defining chapter in conservation and animal behaviour science. For more than sixty years, she fought for primates, wild places, and the people who share those landscapes.

In a statement released early Wednesday, the institute called her loss profound. “Dr. Goodall’s discoveries as an ethologist revolutionized science, and she was a tireless advocate for the protection and restoration of our natural world.”

Even in her nineties, she kept a relentless schedule. Days before her death, she spoke to a full hall at the University of California, Los Angeles, urging students to hurry their climate work. “I have to speed up because I don’t know how many years I have left,” she joked, mixing urgency with warmth in her usual way.

Born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on 3 April 1934 in London, she grew up in a modest home where a love of animals came early. As a child, she hid in a henhouse to watch a hen lay an egg, and only emerged at dusk.

That patience foreshadowed the immersive style that later defined her research. With no university degree at the start, she took a secretarial course, waited tables and modelled to save for a trip to Kenya in 1957. There she met the archaeologist Louis Leakey, whose interest in human origins matched her own curiosity about animal minds.

Jane Goodall’s Study of Chimpanzees

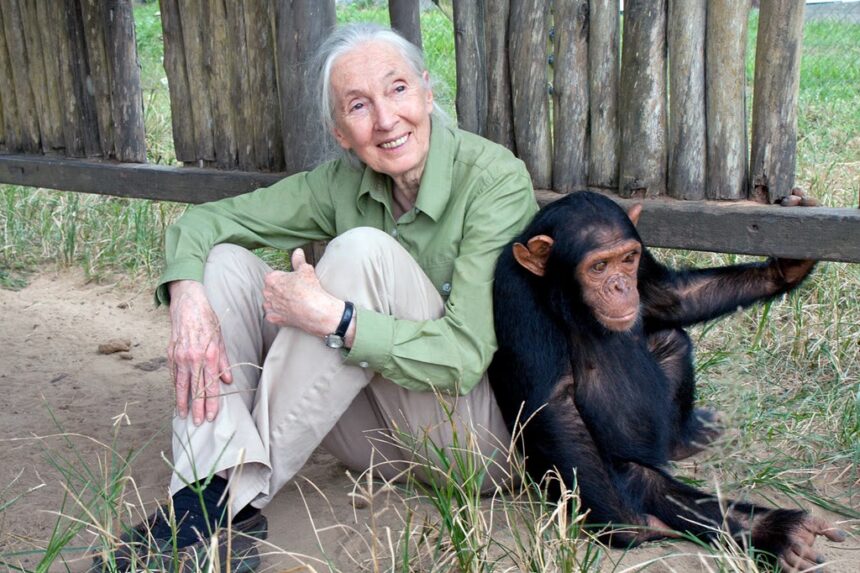

Leakey quickly saw her potential and arranged for her to study chimpanzees at Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve in what was then Tanganyika, now Tanzania. She arrived in July 1960 at age 26, carrying binoculars, a notebook, and steely resolve.

The chimps avoided her for months. She kept going, hiking the hills, sleeping in basic tents, and learning the terrain. In October, a male she named David Greybeard stripped leaves from a twig to fish for termites. It was simple tool use that overturned long-held dogma. Scientists had insisted that making and using tools was a human trait. Her records proved otherwise.

A landmark National Geographic feature in 1963 brought her work to the world. The 37-page story portrayed chimp families in rich detail, with vivid profiles of individuals like Flo and her offspring Fifi and Flint.

It helped readers see chimps as sentient beings with bonds, emotions, and complex lives. “She showed us that chimpanzees are not just ‘animals’ but beings with emotions, intelligence, and complex social structures,” said Dr. Anne Pusey, a long-time collaborator and professor emerita at Duke University.

Jane Goodall’s Gombe findings revealed striking links between chimp and human behaviour: hunting and meat-eating, cooperation, displays in rainstorms, and violent raids that she called “chimpanzee wars.”

These insights challenged human-centred thinking and secured her a PhD in ethology from Darwin College, University of Cambridge, in 1965, even though she had no undergraduate degree. “Cambridge was scandalized at first,” she later said with a laugh. “They made me rewrite my thesis to use ‘he’ instead of ‘it’ for the chimps. But I stood my ground.”

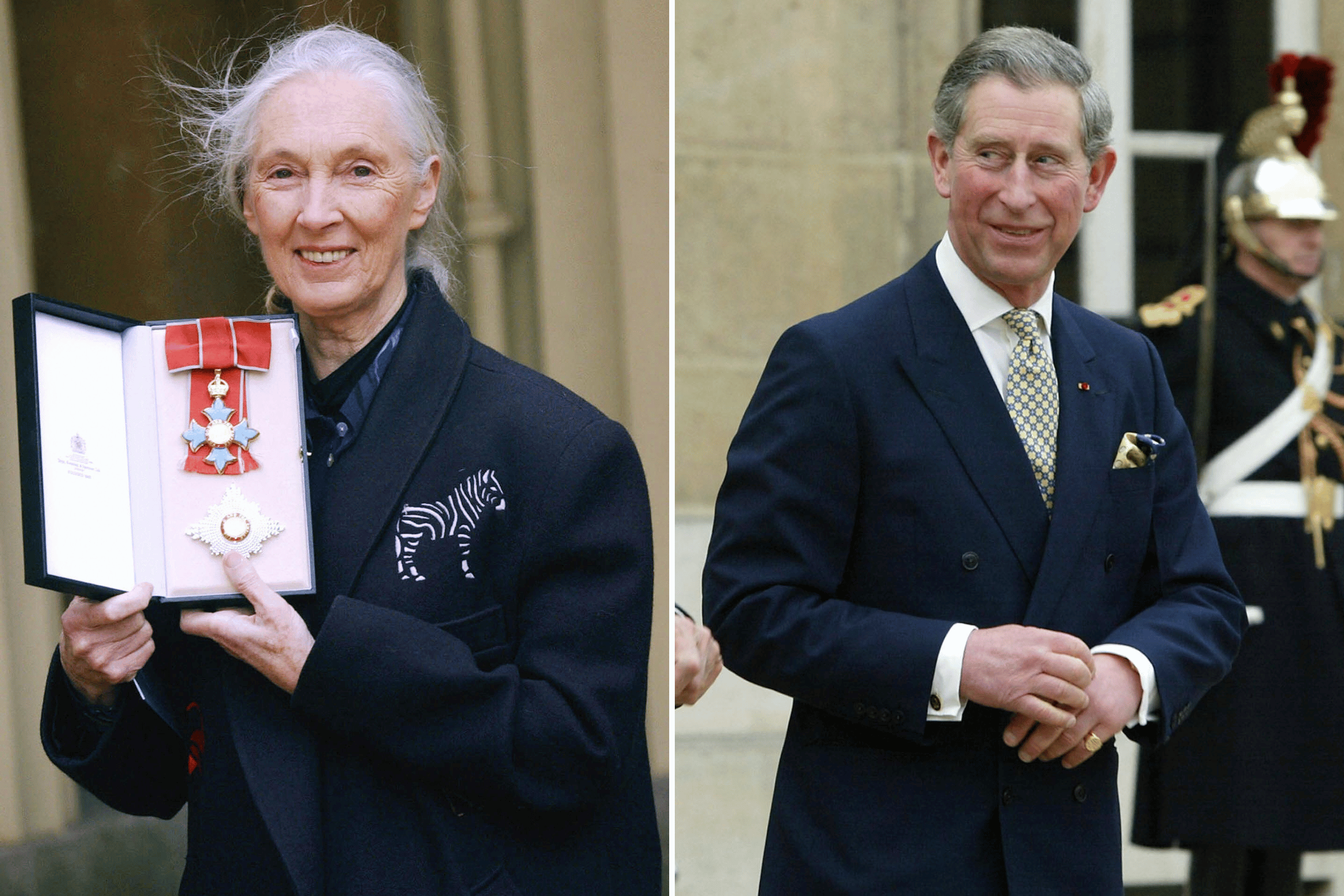

Jane Goodall’s Honours

Honours followed in steady succession, as did the field notebooks she filled under Gombe’s trees. Jane Goodall became a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1974 for her conservation service. The Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences came in 1990. UNESCO named her a Messenger of Peace in 2002. France awarded her the Légion d’honneur in 2004.

Time listed her among the 100 most influential people in 2003 and 2011. In 2015, the United Nations Environment Programme presented its Champion of the Earth Lifetime Achievement Award. At 87, in 2021, she received the Templeton Prize, worth $1.5 million, for work that bridged science and spirit. She directed the funds to youth-led conservation.

Her reach went far beyond academia. In 1977, she founded the Jane Goodall Institute in San Francisco, frustrated by the slow pace of change. The small nonprofit grew into a global organization with offices in 34 countries. It focuses on research, habitat restoration, and community-led conservation.

The Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Center in the Republic of the Congo has rescued and cared for hundreds of orphaned chimps affected by poaching and logging. Roots & Shoots, launched in 1991, now engages more than 100,000 young people across 160 countries on local projects, from tackling plastic waste to fighting wildlife trafficking.

Her advocacy was direct and relentless. She campaigned against the bushmeat trade that has slashed wild chimp numbers to fewer than 350,000, down from millions a century ago. She condemned unethical laboratory testing on primates. “Chimpanzees share 98.8% of our DNA,” she often said.

“How can we justify caging them?” Even into her eighties and nineties, she spent about 300 days a year on the road, speaking at TED, the United Nations, and schools. Her books, including In the Shadow of Man (1971) and Hope and the Human Future (2025), sold widely and blended science with personal narrative.

King Charles III Responds

Though her body aged, her energy did not. In a 2024 BBC Wildlife interview on turning 90, she said, “Age is just a number. The planet needs us all, young and old, to act now.” Her last public talk on 29 September in Los Angeles drew a standing ovation. She shared stories from Gombe and warned of a looming biodiversity crash. “We have a window, but it’s closing fast,” she told the audience.

News of her death raced across the globe, bringing tributes from leaders, scientists, and fans. King Charles III released a message from Buckingham Palace: “Dame Jane was a beacon of hope in our darkening world.

Her work with chimpanzees not only illuminated the animal kingdom but reminded us of our shared responsibility to protect it. She leaves a legacy that will inspire generations, and my family joins the world in mourning her.”

Former U.S. President Barack Obama, who welcomed her to the White House in 2014, wrote: “Jane Goodall taught us to see the world through the eyes of a chimp, and in doing so, to better understand ourselves. Her curiosity and compassion changed science and saved species. Rest in peace, friend.” The post drew more than half a million likes within hours.

Peers offered their own memories. Birutė Galdikas, a protégé of Dian Fossey and one of Leakey’s “Trimates,” said in a JGI video tribute, “Jane was my mentor, my sister in the wild. She showed women like us that passion trumps pedigree.

Gombe will never be the same without her watchful eyes.” Sir David Attenborough told the BBC she was “the most important figure in modern conservation.” He added, “Jane didn’t just observe nature; she communed with it. Her loss is a wound to the soul of science.”

Conservation Groups Pay Tribute

Scientists echoed those sentiments. Dr. Jane Waterman of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute wrote, ” Jane Goodall’s rejection of numbered subjects, naming her chimps instead, humanized primatology and opened doors for ethical research.

She was a pioneer who made room for all of us.” Primatologist Frans de Waal reflected, “Jane’s work proved intelligence isn’t human-exclusive. She was the spark that ignited animal cognition studies.”

Conservation groups paid tribute as well. The World Wildlife Fund, where she served on the board, said, “Her voice amplified the voiceless, from Gombe’s forests to global policy tables. We honor her by redoubling our efforts.” The International Union for Conservation of Nature announced a new “Jane Goodall Grant” to support early-career female researchers, funded by members.

Friends and family recalled her playful side. Grub, the toy chimp she carried from childhood, went with her everywhere, a cheerful reminder of a lifelong bond. Her son, Hugo van Lawick, 59, the filmmaker who captured her early Gombe years, shared, “Mother lived for the chimps, but she loved fiercely too, family, friends, the earth. She whispered to me last week, ‘Keep watching the trees.’ I will, Mum.”

She is survived by Hugo, her sister Judy Moorjani, three grandchildren, and countless chimps adopted through JGI programmes. A private funeral will be held in Tanzania. A public memorial is planned for November in London. The institute asks supporters to donate to Roots & Shoots in place of flowers.

Her message remains her legacy: hope comes from action, especially led by young people. In her final book, she wrote, “Only if we understand, will we care. Only if we care, will we help. Only if we help, shall we be saved.” Jane Goodall did not only study chimpanzees, she reminded people how to be more human. The red earth of Gombe still holds her footprints, and they continue to lead the way.