BEIJING – China has moved to strengthen its oversight of taxes on profits earned from overseas investments, applying a 20% tax on income from offshore trading. This more assertive approach aims at both high-net-worth and middle-income investors, as Beijing looks for new sources of revenue.

The country continues to face economic headwinds, with a prolonged property slump, rising budget shortages and the cost of recent stimulus programs weighing on government finances.

The renewed focus on offshore profits shows China’s determination to steady public finances while supporting President Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” programme to narrow income gaps. Tax legislation from 1980 requires Chinese residents to report and pay taxes on global sources of income, including salaries, dividends and capital gains.

Historically, enforcing these rules on money held abroad proved difficult because authorities lacked reliable data and struggled to coordinate internationally.

Common Reporting Standard

This began to shift in 2018, when China joined the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard, making it easier to swap financial information with over 100 other countries and crack down on tax evasion.

Improved data tools and closer international cooperation now let the State Taxation Administration spot non-compliance more effectively, especially among those trading shares listed in the US and Hong Kong.

Tax offices in major centres like Beijing, Shanghai and Zhejiang have recently contacted individuals about undeclared overseas income.

In March 2025, after reviewing large sets of financial information, officials identified instances where profits had not been reported, spurring tax offices to remind residents to declare assets ahead of the 30 June 2025 deadline for 2024 earnings.

Even those with modest holdings, not just the ultra-wealthy, have faced demands for unpaid taxes and fines, sometimes around 127,200 yuan (£13,900). Previously, authorities focused mainly on households with more than $10 million in assets, but the net has now widened.

This tougher stance comes as China’s financial health shows signs of strain. Central government revenue dropped by 1.3% in the first four months of 2025, while spending jumped by 7.2%. During this time, Bloomberg calculated that the budget gap soared to $360 billion.

The property sector, once a key provider of government income through land sales, has struggled, leaving many local authorities with higher debt and less money coming in. Efforts to revive domestic demand, such as cheaper mortgages and easier home buying rules, were introduced to offset the impact of US tariffs, but these steps add pressure on a budget already stretched thin.

China’s Tax Campaigns

Recent tax campaigns have caused unease among investors and tax advisers. Wu Libin, a specialist in the field, pointed out that current rules do not say whether losses from foreign investments can balance out future profits.

In contrast, domestic A-share trading hasn’t drawn personal income tax since the 1990s, while overseas profits now face a fixed 20% rate and no option to carry over losses to a later year.

Ye Yongqing, a partner at King & Wood Mallesons, said his firm has seen a noticeable rise in questions about foreign income taxes, as more people pay attention to what they need to report. “These laws have existed for years, but the authorities now have better information and coordination, making enforcement much more visible,” he said.

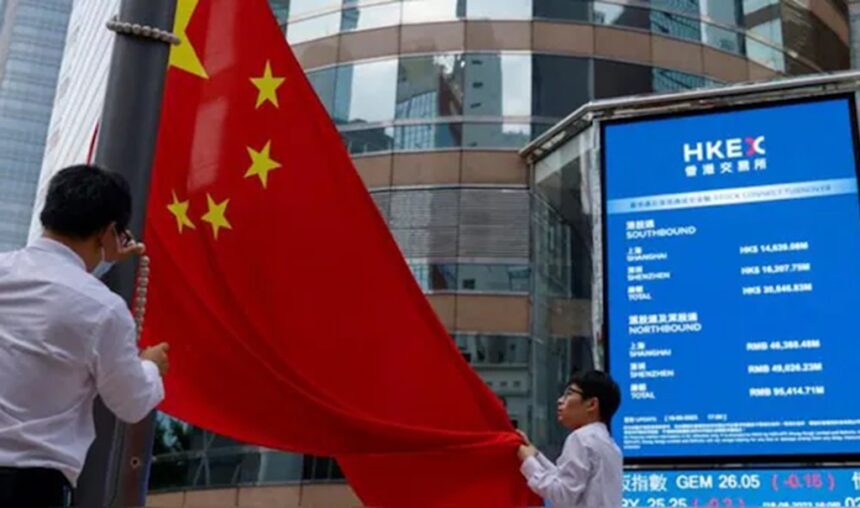

Beijing’s focus fits with President Xi’s “common prosperity” push, which tries to close income gaps by bringing more money into government coffers. As more Chinese investors shift capital offshore—Bloomberg reported that individuals from mainland China put over HK$658 billion (£66.2 billion) into Hong Kong stocks in 2025, more than twice the amount sent abroad in 2024—the authorities have become keen to ensure some of these gains stay at home.

Analysts expect that by 2030, China’s financial assets could reach $80 trillion, with funds outside the country making up 11% of household wealth, compared to 8% in 2023. No surprise, then, that tax officials are showing greater interest in offshore revenues.

The new push on taxes carries its risks. Some specialists warn that tougher enforcement could lead to new outflows at a time when China wants to keep investor confidence high.

Filling State Coffers

Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis, told Asian Private Banker that offshore tax measures could help fill state funds, but strict actions could drive assets and investors away, putting more strain on growth prospects.

“The recent crackdown could encourage people to keep their wealth in China, but may also discourage others from investing altogether,” she noted.

Some investors and wealthy families are already changing their approach. Reports show many are worried about Chinese brokers handing over client data to the authorities, prompting a rethink of investment strategies.

Major cities have seen tax departments summon individuals for interviews about undeclared assets, sometimes going over unpaid taxes for earlier years, imposing the standard 20% tax on profits plus penalties. Shanghai lawyer Peter Ni at Zhong Lun Law Firm noted that tighter checks on personal income tax are likely to continue, with a sharp focus now on offshore income.

Beijing now faces the challenge of raising tax revenue without chasing investors away. The balance between plugging budget holes and supporting business confidence has become more delicate.

The government’s use of modern data systems and global data exchange points to a new phase in tax collection, one that reaches beyond the wealthiest families and brings a much wider group of investors into view.

Whether this will boost funds without creating new economic risks will become clear with time. For now, the message from tax officials is simple: even the smallest overseas profit is on the radar.