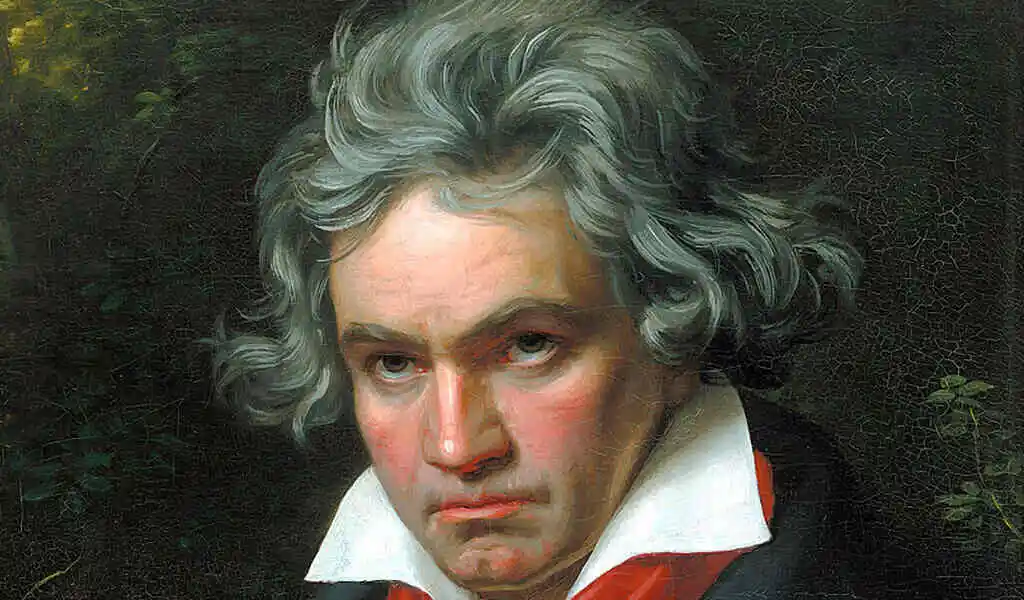

The Heroic Style Of Revolutionary Beethoven!

As we approach the two hundred and the fifty-year anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, we are confronted with somewhat of a paradox: his music is loved and admired all over the world, perhaps more than those of any other composer, despite the fact that its true significance is rarely mentioned except in critical studies that are largely unread by the general public.

It appears that familiarity has not created disdain but rather ignorance. We hear the well-known tunes for the thousandth time, whether in movies, advertisements, or concerts, and they are from the third, fifth, sixth, or ninth symphonies, as well as from piano concertos and sonatas, as well as from chamber music pieces. The sharp edge of this music, on the other hand, has been softened as a result of its widespread use.

That is, we have forgotten, and it appears that we no longer hear Ludwig Van Beethoven’s music’s extremely political nature—its subversive, revolutionary, profoundly democratic, and freedom-exalting nature—and we no stop hearing it.

The primary theme of the first movement is based on it as well before Beethoven throws the music off course with such a chromatic slant that it appears to be intentional. The fact is, though, that this twist embodies the whole character of this movement: every notion is always in flux.

While it has characteristics of conflict, contrast, and growth, it goes much beyond what one might expect from a “sonata form,” though those components are clearly present; it is simply that the development never comes to a halt. For example, according to Jan Swafford’s recently published biography of the composer, “This will be music describing the process of being.” Another aspect that is both abstract & symbolic is the Hero’s aspiration for a certain goal. “Call it a win; call it the realization of one’s own identity.” The

The second movement is a funeral march in the traditional sense.

However, the fundamental question is why the second movement is indeed a funeral march in the first place. Despite his advanced age (he was one year older than Beethoven), Napoleon was still very much alive and well, and the bloodiest of his several military conflicts remained ahead of him. Because of this, the commonly held belief that Beethoven was picturing the death of his (then) hero appears to be a little strange.

It is questionable whether or not this had any personal importance for him outside of its merely musical value. He began to go deaf in his twenties for reasons that are unclear – possibly due to an infection of some kind, possibly due to otosclerosis, perhaps due to something else entirely. He reached a crisis point in 1802 as he struggled to come to terms with his deteriorating condition, and he died as a result of his efforts.

According to the so-called ‘Heiligenstadt Testament,’ he admitted to his two brothers that he would have pondered killing himself: “Only my work kept me from doing it… ” It seems to me that I would be unable to leave the earth until I had brought forth what I believed was contained inside me.” The possibility that he was burying himself in the funeral march of the symphony is not completely out of the realm of possibility.

The symphonic form had traditionally been associated with feelings of tension and conflict. However, in this symphony, these characteristics are emphasized to an unprecedented degree. The piece begins with two very loud and abrupt chords, which, inside the words of Leonard Bernstein, “broke the elegance of the eighteenth century.” It is often harmonically unstable, yet there is a persistent sense of forwarding motion all through the rest of the movement, which is a mix that can be seen throughout his mature compositions.

This symphony was dedicated to Napoleon, but Ludwig Van Beethoven famously removed the dedication after learning that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor of the world. The composition was eventually given the title Eroica (which means “heroic” in Latin).

We find it fascinating that Beethoven’s rebirth from a severe melancholy was not manifested in an introspective or simply personal manner, as was customary among Romantic musicians in the nineteenth century, but instead just via optimism engendered by the prospect of revolutionary upheaval in Europe.

Beethoven’s confidence in revolutionary ideas was thought to have been extinguished with the removal of the dedication to Napoleon; however, this was far from the reality, according to scholars. There are several scattered allusions in his writings throughout his life that indicate he still believed in the abolition of aristocratic and ecclesiastical authority at the time of his death.

Also Check:

7 Gifting Ideas To Surprise Your Love

Bridal Asia Event 2022, A Paradise For Every New Bride

101 How To Buy Land In Metaverse 2022.

How to Create a Cool Vibe at Your Next Party